government: theocratic republic

state of civil and political rights: Not free

constitution: 2-3 December 1979; revised 1989 to expand powers of the presidency and eliminate the prime ministership

legal system: based on Sharia law system

legislative system: Unicameral Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majles-e-Shura-ye-Eslami)

judicial system: Supreme Court

religion: Shia majority; 10% Sunni; Christian, Jewish, Baha'i and Zoroastrian minorities

death row:

year of last executions: 0-0-0

death sentences: 6

executions: 800

international treaties on human rights and the death penalty:International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Statute of the International Criminal Court (which excludes the death penalty) (only signed)

situation:

In accordance with Article 4 of the Iranian Constitution, Islamic law is “the

essential source for all the branches of legislation”, including civil and

penal legislation.

Offences punishable by death include: murder; armed robbery; rape; blasphemy; apostasy;

adultery; prostitution; homosexuality; drug-related offences and plotting to

overthrow the Islamic regime, kidnapping, treason, espionage, terrorism,

economic crimes, military offences.

Iranian law imposes the death penalty for possession of more than 30 grams of

heroin or five kilos of opium. Iranian authorities say that most of the people

put to death in the country are convicted of drug-related crimes, but human

rights observers believe that many of the people put to death in Iran for ordinary

crimes, particularly drug crimes, may well be in fact political opponents.

Under Iran's strict Islamic law, consuming alcohol is forbidden for Muslims and

usually punishable by lashes or fines. An offender caught for a third time,

however, can be sentenced to death.

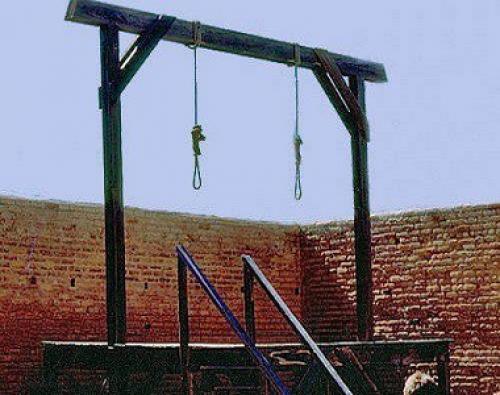

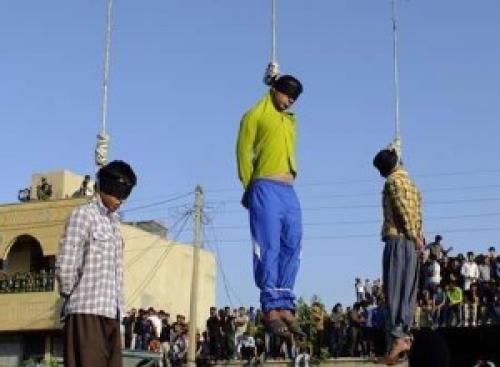

Hanging is the preferred method with which to apply Sharia law. It is often carried out by crane or low

platforms to draw out the pain of death. The noose is made from heavy rope or

steel wire and it is placed around the neck in such a fashion as to crush the

larynx causing extreme pain and prolonging the death of the condemned. Hanging

is often carried out in public and combined with supplementary punishments such

as flogging and the amputation of limbs before the actual execution.

On 12 July 2011,the Japanese company Tadano said it had ended contracts with the Iranian government following a

report that its cranes had been used for public executions. Just days after United

Against Nuclear Iran President Mark Wallace penned a 6 July opinion article

in the Los Angeles Times stating that Tadanowas one of several companies selling

cranes to Iran; as a result, the company announced it would cease making further deals with

the Iranian government. “No one should be having their products going to

Iran, particularly given the Iranian regime’s history of misusing products and

money to fund terrorism,” UANI communications director Nathan Carleton said.

UANI has launched a Cranes Campaign, publishing on its website a list of eight

international companies that send crane resources to Iran, with photos of the

cranes being used as execution devices.

On 8 August 2011, another Japanese crane manufacturer, UNIC, announced the end

of its business in Iran, joining Tadano and

Terex in pulling out of Iran

following UANI’s Cranes Campaign. UNIC officials wrote to UANI, stating that

UNIC will not sell any more products to Iran, or derive any revenue from Iran,

and “will not accept orders for any of our products if such products are known

to be destined for Iran.”

In April 2013, the Guardian Council of Iran, an unelected body of 12 religious jurists empowered

to vet all legislation to ensure its compatibility with Iran’s Constitution and

Sharia, reinserted execution by stoning for

those convicted of adultery into a previous version of the new Penal Code which had

omitted it.

In February 2013, the spokesman for the Iranian Parliament Justice Commission, Mohammad Ali Esfenani,

told reporters that the punishment of stoning was removed from the Iranian Penal

Code due to negative international attention. He said: “Some people in the

international arena have a very biased view of stoning and use it against Iran.

They mean that stoning is a violation of human rights.” He added: “Stoning is

only removed from the law but it still exists in Sharia and cannot be

removed from the Sharia.”

However, the draft Penal Code, as amended by the Guardian Council, explicitly identifies stoning as a form of

punishment for people convicted of adultery or sex outside of marriage. Under

Article 132, paragraph 3, of the new version of the Penal Code, a man or a

woman can be stoned to death for multiple extramarital affairs. In addition,

under article 225, if a court and the head of the judiciary rule that it is

“not possible” in a particular case to carry out the stoning, the person may be

executed by another method if the authorities proved the crime on the basis of

an eyewitness' testimony or the defendant’s confession.

The revised code also provides that courts that convict defendants of adultery

based on the “knowledge of the judge,” a notoriously vague and subjective

doctrine allowing conviction in the absence of any hard evidence, may impose

corporal punishment sentences of 100 lashes rather than execution by stoning.

The penalty for people convicted of fornication, or sex outside of marriage

that involves an unmarried person, is 100 lashes.

For the execution by stoning, the condemned person is wrapped head to foot in

white shrouds and buried in a pit. A woman is buried up to her armpits, while a

man is buried up to his waist. A truckload of rocks is brought to the site and

court-appointed officials, or in some cases ordinary citizens approved by the

authorities, carry out the stoning. Article 104 of the Penal Code states that

"the stones should not be too large so that the person dies on being hit

by one or two of them." If the condemned person somehow manages to survive

the stoning, he or she will be imprisoned for as long as 15 years but will not

be executed.

Iran has the world’s highest rate of execution by stoning, but no one knows with certainty how many people

have been stoned in Iran.

According to a list compiled by the Human Rights Commission of the National Council of the Iranian

Resistance, at least 150 people have been stoned in Iran since 1980. The

reported numbers are probably lower than the actual numbers, because most of

the condemnations to stoning issued by the Iranian authorities are handed down

secretly, as well as for the fact that so little information is actually

available from many prisons in Iran. Shadi Sadr, who has represented five

people sentenced to stoning, said Iran carried out stoning in secret in

prisons, in the desert or very early in the morning in cemeteries.

The approval of the new Islamic Penal Code in 2013 might lead to more death penalties for

apostasy. The Constitution states that Ja’afari (Twelver) Shia Islam is the

official State religion. It provides that “other Islamic denominations are to

be accorded full respect” and officially recognises as religious minorities

only three non-Islamic religious groups, Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews.

Although the Constitution protects the rights of members of these three religions to

practice freely, the Government imposed legal restrictions on proselytising.

Seeking to convert Muslims to Christianity or other religions is considered a

crime, although Christians are allowed to convert to Islam. Converts to

Christianity from Islam are often harassed and persecuted and forced to gather

in home churches, while Christian missionaries are routinely expelled and

sometimes jailed for distributing Bibles and other religious material.

Repression of nearly all non-Shia religious groups – most notably Bahais, as well as Sufi

Muslims, evangelical Christians, Jews, and Shia groups not sharing the

Government’s official religious views – increased significantly in the past few

years. Bahai and Christian groups reported arbitrary arrests, prolonged

detentions, and confiscation of property.

The Government considers Bahais to be apostates and defines the Bahai Faith as a

“political sect.” The Government prohibits Bahais from teaching and practicing

their faith and subjects them to many forms of discrimination not faced by

members of other religious groups. Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the

Government has executed more than 200 Bahais.

In recent years, a Government crackdown on religious minorities has intensified. Several

churches in Iran were shut down and a number of converts from Muslim background

were arrested and detained. Under Sharia law, the sentence of apostasy

is death, but apostasy is not explicitly mentioned in the new Islamic Penal

Code. However, the new law makes it easier for judges to issue the death

penalty for apostasy because Article 220 of the new Code states: “If the

present law is silent about any of the Hudud cases, the judge is referred to

article 167 of the Constitution.” Article 167 of Iran’s Constitution

explains: “The Judge is bound to attempt to rule on

each case, on the basis of the codified law. In case of the absence of any such

law, he has to deliver his judgment on the basis of official Islamic sources

and authentic fatwa. He, on the pretext of the silence of or deficiency

of the law in the matter, or its brevity or contradictory nature, cannot

refrain from admitting and examining cases and delivering his judgment.” The

reference to article 167 was previously made in the Civil Code but now it is

also included in the Penal Law.

Furthermore, in the new Penal Code approved in its latest version by the Guardian Council in

April 2013, the term “homosexual” is presented as a charge in the new law for

men who engage in same-sex relations. Previously it was only used for women. In

any case, sexual relations between two individuals of the same sex continue to

be considered Hudud crimes, and to be subject to punishments from one

hundred lashes to execution.

According to Article 233 of the new code, the person who played an active role (in sodomy)

will be flogged 100 times if the intercourse was consensual and he was not

married, but one that has played a passive role will be sentenced to death

regardless of his marital status. If the active part is a non-Muslim and the

passive part a Muslim, both will be sentenced to death. In accordance with

Articles 236-237, homosexual acts (except for sodomy) are punished with 31-99

lashes (both for men and women). According to Article 238, an homosexual

relationship between women where there is contact between their sexual organs

will be punished with 100 lashes.

In January 2008, then-judicial chief Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi decided that public

executions, in the future, would be carried out “only with his approval and

based on social necessities.” In fact, public executions decreased in 2008,

when there were no less than 30 public hangings, of which 16 took place after

Shahroudi’s decree; besides, no less than 12 people were hanged in public

places in 2009, compared to at least 110 people who were publicly executed in

2007.

However, since the 2009 post-election

protests in Iran, the number of executions, particularly public executions, has risen dramatically. In 2010, at least 19

people were hanged publicly. In 2011, public executions have more than tripled,

with at least 65 people being executed in public. According

to Iran Human Rights, in 2012 there

were at least 60 public executions,

a number six times higher than numbers from 2009, when at least 12 people were

hanged in public places. The trend has continued in 2013. The number of

public hangings and other public punishments, including flogging and

amputations, increased significantly at the approach of the presidential

elections of June 2013.

The election of Hassan Rouhani as President of the Islamic Republic on 14 June 2013 had led many observers,

some human rights defenders and the international community to be optimistic.

However, the new Government has not changed its approach regarding the

application of the death penalty, and indeed, the rate of executions has risen

sharply since the summer of 2013.

In 2014 the Islamic Republic

carried out at least 800 executions, a 16.5% increase compared to 687 in

2013: 290 execution cases (36%) were reported by official Iranian

sources (websites of the Iranian Judiciary, national Iranian broadcasting

network, and official or state-run news agencies and newspapers); 510

cases (64%) included in the annual numbers were reported by unofficial sources

(other human rights NGOs or sources inside Iran).

According

to Iran Human Rights (IHR), in 2014 the Islamic Republic carried out at

least 753 executions: only 291 execution cases were reported by

official Iranian sources. Iran Human Rights emphasises that the actual

number of executions is probably much higher than the figures included in its

report.

A majority of those who were executed were convicted of drug-related

offences (371 cases, 125 of them reported by official Iranian sources),

followed by murder (247 cases, including 119 announced by official sources),

rape (32 cases, of which 30 announced by official media), non-violent or

clearly political offences (32 cases, including 8 officially reported), and Moharebeh

(waging war against God), armed robbery and “corruption on earth” (31 cases,

including 11 officially reported). In at least 100 other cases, the crimes

which the convicts were found guilty of remained unspecified.

This

trend has continued also in 2015 which began with a series of mass

executions. According to Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (IHRDC),

as of June 18, at least 342 executions were carried out in Iran,

including 125 announced by the Government.

In 2014, executions of women have slightly decreased: there were

266 were

announced by Iranian authorities. In 2013, Iran had hanged at least 30 women.

However, executions of child offenders doubled in 2014, in open violation of two international

treaties to which it is party, the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, both of which

outlaw the execution of people who had committed their crimes when they were

under the age of 18. bAt least 17 juvenile offenders were hanged

in 2014 (15 for murder cases, including 3 reported by official sources; and 2

for drug-related crimes). The execution of child

offenders had continued into 2012 and 2013. An alleged juvenile offender was

executed in public in March 2012, according to Amnesty International. Another

two possible minor offenders were executed in

2013 (in January and February). At least 4 people were hanged in 2011, after

being convicted of offences they had allegedly committed when they were under

the age of 18. At least 2 juvenile offenders were hanged in Iran in 2010 and at

least 5 in 2009.

Under Iranian law, girls above nine years of age and boys over 15 are

considered adults, and therefore can be condemned to death. Iranian authorities

generally wait for young convicts to reach their eighteenth birthday before

ordering their execution.

Following requests – ignored for years – to stop death sentences handed

down for all convicts accused of committing crimes as minors, the Mullah’s

regime announced a partial and, in reality, insignificant revision of the

Iranian norm, once again, out of step with the international community.

The regime

claims that the new Penal Code – which was approved in its latest version by

the Guardian Council in April 2013 – abolishes the execution of children under

eighteen. However, under Articles 145 and 146 of the new Penal Code, the age of

criminal responsibility is still “puberty,” meaning nine lunar years for girls

and fifteen lunar years for boys. Thus, the age of criminal responsibility has

not changed at all in the new Penal Code.

Under

Article 87 of the new Penal Code, the death sentence has been removed for

juveniles only in Ta’zir crimes (such as drug offences), whose

punishment can be administered at the discretion of the judge. Under the same

law, however, a death sentence may still be applied for a juvenile if he or she

has committed offenses whose punishments have been specified in the Sharia:

Hudud crimes,that are defined as “claims of God” and

therefore have mandatory sentences (such as sodomy, rape, fornication,

apostasy, consumption of alcohol for the fourth time, Moharebeh (enmity

against God), and “spreading corruption on earth”); Qisas crimes (such

as murder), that are defined as “claims of [His] servants” and where

responsibility for prosecution rests on the victim, which are treated as

private disputes between the murderer and the victim’s heirs who are given the

right to demand the execution of the murderer (Qisas), or forgive him or demand

compensation (Diya).

In fact, article 90 of the new

Penal Code stipulates that legally “mature” individuals under eighteen (i.e.,

boys between the ages of fifteen and eighteen and girls between the ages of

nine and eighteen) who are convicted of Hudud and Qisas crimes

may be exempted from adult sentences – including the death penalty – only

if it is established that they were not mentally mature and developed

at the time of committing the crime, and could not recognize and appreciate the

nature and consequences of their actions. Therefore, this article gives judges

the discretion to decide whether a child has understood the nature of the crime

and therefore whether he or she can be sentenced to death.

The

use of the death penalty for non-violent or clearly political offencescontinued in 2012. In 2014, at least 32 people were hanged. In such cases, executions

are often carried out in secret, without lawyers or family members being

informed. However, among those condemned to

death for ordinary crimes or for “terrorism” or those executed for Moharebeh

and/or “corruption on earth”, many people are

not directly involved in acts of violence: many of them are in fact political

dissidents, members of banned groups or members of

Iran’s ethnic and religious minorities, including Iranian Azerbaijanis, Kurds,

Baluchis, and Arabs. Accused of being Mohareb

– enemies of Allah – those arrested are often subjected to rapid and severe trials that often end

with death sentence. The punishment for Moharebeh

is death or amputation of the right hand and left foot, according to the

Iranian Penal Code. According to Iran

Human Rights, at least 23 (3%) of 294 people who were executed in 2012

according to the official Iranian sources were convicted of Moharebeh (war against God).

Iranian law provides for the death penalty in cases of possession of more than 30 grams

of heroin or 5 kilos of opium.

In December 2010, a new anti-drug law came into effect extending the death

penalty to possession of other types of illegal substances such as

methamphetamine.

In Iran drug-related offences are tried in Revolutionary Courts, which

routinely fall far short of international fair trial standards. Revolutionary

Court trials are frequently held behind closed doors and judges have the

discretion to restrict lawyers’ access to the defendant during pre-trial

investigations in limited cases. Under Article 32, death row prisoners

convicted on drug-related offences do not have the right to appeal. Only the

Attorney General or the head of the Supreme Court can appeal the death sentence

for such convictions.

Since the vast majority of those executed for drug-related charges are not identified by last (family)

name, it is not possible to confirm the charges. Human rights observers believe

that many of those executed for common crimes such as drugs are actually

political dissidents.

On 9 April 2013, Danish newspapers reported that the Danish government had decided to cut its aids to

Iran’s anti-drug program. Denmark was one of several western countries

providing financial aid to Iran’s war on drugs. The aid is provided to Iranian

authorities through the UNODC (United Nation’s office for drugs and crimes). In

the past few years several human rights organizations have urged the UNODC and

donor countries to stop contributing indirectly to the increase in executions

in Iran. Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom have all

chosen to withdraw their support from Iranian counter-narcotics operations

administered by the UNODC because of concerns that this funding was enabling the

execution of alleged drug traffickers. When announcing its decision to do so,

Denmark and Ireland publicly acknowledged that the donations are leading to

executions. Danish

newspaper Politiken reported that

"Denmark has for the past two years

given five million dollars annually to a counter-narcotics program in

Iran." “During the same period, the Iranian authorities executed hundreds

of suspected drug offenders, and on this basis, Development Minister Christian

Friis Bach (Radikale) has now decided to immediately discontinue support for

the program”, reported Politiken. “It

is a signal to Iran that the use of the death penalty is unacceptable and

something that we in no way can vouch for”, he told Politiken.

However, the

UNODC leadership doesn’t appear to be at all bothered by the fact that its

funds are used by the Iranian authorities to execute “drug offenders” at such

devastating rate.

On 11 March

2014, the U.N. anti-drugs chief praised Iran’s fight against narcotics

trafficking despite a surge in executions in the country, many of which due to

drug-related offences. Yury Fedotov, executive director of the U.N. Office on

Drugs and Crime (UNODC), said the Vienna-based agency opposes the death

penalty, “but on the other side, Iran takes a very active role to fight against

illicit drugs.” In 2012, Iran seized 388 metric tons of opium, the equivalent

of 72 percent of all such seizures around the world. “It is very impressive,”

Fedotov told reporters before an international meeting in Vienna on March 13-14

on global efforts to combat narcotics. Fedotov made clear the UNODC was not

considering halting support for Iran. “I don’t believe that the international

community would welcome this because it would mean, as a possible reaction from

Iran, that all these huge quantities of drugs, which are now being seized by

Iranians, would flow freely to Europe,” he said.

On 18 November 2014, Iranian Justice Minister Mostafa Pourmohammadi lashed out at the

so-called western advocates of human rights for their opposition to the

punishment of drug trafficker in Iran. "We do not accept the statements

made by the UN human rights bodies that drug-related convicts should not be

executed," Pourmohammadi said. He underlined that anyone who smuggles and

distributes narcotics deserves to be executed.

On 4 December 2014, Mohammad Javad Larijani, the secretary of Iran’s Human Rights

Council, said that Iran is looking to end the death penalty for drug related

cases, which he said account for 80% of the country’s total executions. In an English-language

interview with France 24’s Sanam Shantyaei, Javad Larijani said, “No one is

happy to see the number of executions is high. And it’s a sad story that we

have this much drug related crime... According to the existing law, they are

receiving capital punishment.” Javad Larijani continued, “We are crusading to

change this law. If we are successful, if the law passes in the parliament,

almost 80% of the executions will go away. This is big news for us, regardless

of Western criticism.” His statements were picked up and translated by Iran’s

Persian-language Fars News Agency. While not speaking as explicitly as Javad

Larijani, Ayatollah Sadegh Larijani, Javad Larijani’s brother and the head of

Iran’s judiciary, addressed the need to change the country’s drug laws. During

a meeting of judiciary officials on December 2, he said, “On the issue of drugs

and trafficking, it feels necessary a change in the legislation because the

ultimate goal of the law should be implementing justice, while in reality this

goal is often not realized.” According to conservative Etelaat

newspaper, Sadegh Larijani did not advocate softness on drug smuggling. He said

that drug smugglers need to be “dealt with seriously” but conceded,

“Unfortunately, today, with respect to drugs and drug-related laws, we see that

these laws have no impact.” This is not the first time that Iran’s judiciary

has proposed changing the punishment for drug-related crimes, or at least

modifying how the punishment is implemented. In May 2014, current deputy head

of Iran’s judiciary Gholam-Ali Mohseni-Ejei, while speaking as the country’s

top prosecutor, said at a meeting of the High Council for Human Rights in Iran:

“Unfortunately, the high number of executions in this country is related to

drugs smuggling and the heavy penalties for this infraction. If, within the

existing laws, we can review them in such a way that we help the intelligence

officials to punish the leaders of these smuggling networks, and for the rest

we reconsider [their punishment], the goals of the system can be better

realized.”

On

18 December 2014, six rights groups – Reprieve, Human Rights Watch, Iran Human

Rights, the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, Harm Reduction

International and the Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation – said the United

Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) should follow its own human rights

guidance and impose "a temporary freeze or withdrawal of support" if

"following requests for guarantees and high-level political intervention,

executions for drug related offenses continue." The UN agency's records

show it has given more than $15 million to "supply control"

operations by Iran's Anti-Narcotics Police, funding specialist training,

intelligence, trucks, body scanners, night vision goggles, drug detection dogs,

bases, and border patrol offices, the groups said. UNODC projects in Iran have

come with performance indicators including "an increase in drug seizures

and an improved capability of intercepting smugglers," and an

"increase of drug-related sentences."

The widespread executions which have taken place inside prisons all over the

country are all carried out in secret, in groups, unannounced, extrajudicially,

and arbitrarily. According to sources who have talked with the International Campaign for Human Rights in

Iran, the group executions inside Vakilabad Prison are carried out by

putting convicts in a line in a roofless hallway leading to the prison’s

visitation hall. The executions are carried out secretly, without the knowledge

or presence of the prisoners’ lawyers and families, who do not find out about

the executions until one or several days later. Even the prisoners themselves

are unaware of their impending execution until a few hours before it is carried

out.

In

Iran, that carries out executions regularly without classifying the death

penalty as a State secret, authorities do not release statistics on the

implementation of death sentences, the names of the hundreds of convicts

executed each year, or the crimes for which they were found guilty.

The main

sources of information on executions are reports selected by the regime and

carried by State media. These reports do not carry news of all executions, and

additional information that occasionally arrives from scattered reports by

Iranian journalists or individual citizens or by political opposition groups,

evidently, cannot cover all the executions throughout the nation.

The Iranian system and its

treatment of information regarding the death penalty became even more opaque

when, on 14 September 2008, the Mullahs’ Ministry of Culture and Islamic

Guidance (MCIG) warned newspaper editors to censor reports about escalating

numbers of executions, in particular those of minors in the country.

The Campaign believes that withholding official announcements of the

said executions is a deliberate effort to conceal the actual statistics of

executions in Iran. Campaign’s

sources have also said that these death sentences are usually issued at the end

of often only few minutes-long trials,

and that the suspects are deprived of a fair trial. Such conditions place these

executions in the category of extrajudicial and arbitrary executions.

“A few specific branches within the Mashad Revolutionary Court review ‘several

drug trafficking cases in each hour,’ without following procedures for a fair

trial or without regard for current Iranian laws, and in many cases the

widespread death sentence decisions are based only on reports from the

Intelligence Office, the IRGC Intelligence Unit, or the Police Intelligence

Unit, or on confessions extracted from

the suspects under severe physical torture, mostly inside police detention

centres. Most, if not all, of the widespread death sentences pertaining to drug

trafficking suspects inside the Mashad Revolutionary Court are issued within only ‘a few

minutes long’ trial, without the presence of the suspect’s selected or

court-appointed lawyers, and they are all upheld and carried out within just a

few months,” a local source told the Campaign.

“In many cases, the death sentences for foreign nationals, and mostly Afghan

suspects, are issued without observing the ‘right to access consular services.’

The suspects’ lack of familiarity with the court’s official language, Farsi,

keeps them from comprehending the judicial process and answering the questions,” added the source.

Iran Human Rights believes that one

of the reasons for the secret mass executions in Vakilabad and other Iranian

prisons is that the prisons are overfilled. According to official Iranian

reports, there are about 600,000 prisoners in the Iranian prisons. IHR’s

sources estimate that there are 20,000 prisoners in Vakilabad, though the

prison only has the capacity to house 4,000 inmates. According to eyewitnesses,

in some of the wards the prisoners have to sleep on the steps and in the corridors.

The situation is similar in several other Iranian prisons, and it seems that

mass execution of the death row prisoners is one of the solutions Iranian

authorities have sought for overcrowded

prisons in Iran. According to unconfirmed reports, there could be as many as

3,000 death row prisoners in Vakilabad in danger of execution in the coming

months.

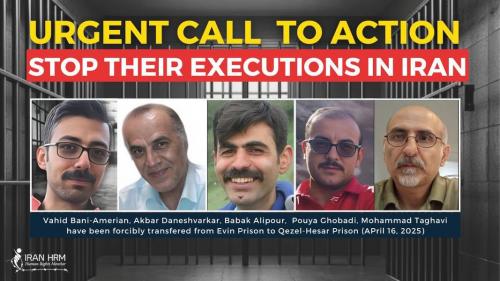

There were also reports of secret and unannounced executions in 15 other

Iranian prisons. The majority of the reports came from prisons in the Tehran/Karaj area: Evin, Ghezel Hesar and

Rajai Shahr.

However, the death penalty is not the only punishment dictated by the Iranian

implementation of Sharia. There is

also torture, amputation, flogging and other cruel, inhuman and degrading

punishments. These are not isolated incidents and they occur in flagrant

violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which

Iran signed and which expressly prohibits such practices.

Every year, thousands of youths are whipped for consuming alcohol or attending

parties with the opposite sex or for outrages against public decency.

Authorities consider whipping an appropriate punishment to combat immorality,

and such punishments are publicly inflicted as a “lesson to those who watch.”

But the regime particularly outdoes itself in its violation of women’s rights.

The segregation of men and women has increased since the first election of

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad who as mayor of the capital first inaugurated the

segregation of men and women in the city’s elevators. Authorities began police

patrols in the capital to arrest women wearing clothes deemed improper.

Hard-liners say that improper veiling is a “security issue” and that “loose

morality” threatens the core of the Islamic republic.

Iranian law provides that the “blood money” (diya) for a woman is half that of a man. Furthermore, if a man

kills a woman, the man cannot be

executed, even if condemned to death, without the family of the woman first

paying to the family of the murderer half the price of his blood money.

On December 27, 2003, after a favourable verdict by the Supreme Leader of the

Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Expediency Council approved a

Majlis bill that guaranteed non-Muslim minorities the right to the same “blood

money” as Muslims, which currently corresponds to 442 million riyal (about

36,000 USD). Under the bill, proposed by Parliament in January

2003, the blood money for recognized religious minorities in Iran - Jews,

Christian and Zoroastrians - has become equal to that of a Muslim Iranian

national. The

blood money for the life of a woman continues, however, to be one half of that

of a man.

Iranian

authorities claim that “We can’t deny a victim’s family of the legal right to

ask for Islamic Qisas, or eye for eye retribution.” Qisas is

probably the only “right” of the Iranian people that the regime insists on

protecting.

However, the Iranian Penal

Code exempts, among others, the following people from Qisas: Muslims,

followers of recognized religions, and “protected persons” who kill followers

of unrecognized religions or “non-protected persons” (Article 310). This

concerns, in particular, members of the Bahai faith, which is not

recognized as a religion, according to Iranian law. If a Bahai follower

is murdered, the family does not receive blood money, and the offender is

exempted from Qisas.

On 28 April

2014, Iran’s Prosecutor General Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejeie said the payment

of “blood money” spared 358 Iranians from execution in the last Iranian

calendar year, between March 2013 and March 2014, the FARS news agency

reported. In April, Iranian media published details of several capital cases in

which blood money spared the killers from execution. The most high-profile case

involved a blindfolded murderer known only as Balal being pictured with a

hangman’s noose around his neck. The convict escaped the gallows at the last

minute when his victim’s mother pardoned him, and only administered a slap on

his face as punishment. The blood money in the Balal case had been raised from

the proceeds of a film director’s special screening, amounting to 3 billion riyals

(90,000 USD). After Balal dramatically escaped death, media reported several

other cases in which the victim’s family pardoned the killer at the very last

minute, with one being pardoned even after he was hanged for a few minutes.

Another fundraising event was the screening of a film called “Sensitive Floor” which

was held by famous actors and artists on 27 April. The organisers managed to

raise 7,000,000,000 riyals (200,000 USD) as blood money which was needed

for three convicts on death row.

Observers say a concerted

publicity campaign is at play, and the regime is already benefiting from the

wave of forgiveness because “it shows a more human face of Iran.” But money is

also a factor. Abdolsamad Khoramshahi, a well-known Iranian lawyer who has

represented several convicted killers, said that what media called a wave of

mercy was in fact a “business.” “Based on the information I have about some of

the cases, I have to say that a large part of the reconciliations in Qisas

(retribution) cases are happening in exchange of enormous sums of money from

the families of those convicted,” Khoramshahi told fararu.com in early

July 2014.

On 22 January 2014,

independent United Nations human rights expert called on the Government of Iran

to urgently halt executions. “We are dismayed at the continued application of

the death penalty with alarming frequency by the authorities,” said the UN

Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Christof

Heyns. He added that the Government was proceeding with executions that did not

meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” as required by international

law. Ahmed Shaheed, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in

Iran, also voiced concern at an increase in executions of political activists

and individuals from ethnic minority groups, saying: “The persistent execution

of individuals for exercising their rights to freedom of assembly, association,

and affiliation to minority groups contravenes universally accepted human

rights principles and norms.” The Special Rapporteurs also urged Iran “to heed

the calls for a moratorium on executions, especially in cases relating to

political activists and alleged drug-offences.” The experts’ appeal was also

endorsed by the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or

degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez.

On 7 March 2014, however, the

head of Iran’s Judiciary Human Rights Council, Mohammad Javad Larijani, said

the Islamic Republic’s execution rate should be viewed as a “positive marker of

Iranian achievement,” and the world should view it as a “great service to

humanity.”

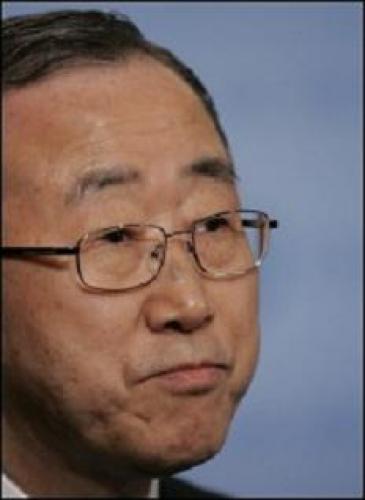

On 11 March 2014, in a report

to the U.N. Human Rights Council, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani had failed to fulfil campaign promises to

allow greater freedom of expression and there had been a sharp rise in

executions since his election. Ban highlighted the prevalent use of capital

punishment in Iran and called for the release of activists, lawyers and

journalists as well as political prisoners that he said were in custody for

exercising their rights to free speech and assembly. “The new administration

has not made any significant improvement in the promotion and protection of

freedom of expression and opinion, despite pledges made by the president during

his campaign and after his swearing in,” Ban said. Ban said that most

executions in Iran were for drug offences, but political prisoners and ethnic

minorities were also among those put to death. “The new government has not

changed its approach regarding the application of the death penalty and seems

to have followed the practice of previous administrations, which relied heavily

on the death penalty to combat crime,” Ban said.

On 18 December 2014, United

Nations General Assembly (UNGA) approved a Resolution expressing deep concern

about the "alarmingly high frequency" of the use of the death penalty

in Iran, including public executions, secret group executions, and imposition

and carrying-out of the death penalty against minors and persons who at the

time of their offence were under the age of 18, in violation of the obligations

of the Islamic Republic of Iran under the Convention on the Rights of the Child

and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The UNGA also

condemned the imposition of the death penalty for crimes that lack a precise

and explicit definition, including Moharebeh (enmity against God), and

for crimes that do not qualify as the most serious crimes, in violation of

international law. The Resolution also criticized the Iranian regime's use of

torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including

flogging and amputations.

On 18 December 2014, Iran

voted against the Resolution on a Moratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty at

the UN General Assembly. Iran had voted against the Resolution also on 20

December 2012.