government: federal republic

state of civil and political rights: Free

constitution: 26 January 1950; amended many times

legal system: based on English common law; limited judicial review of legislative acts

legislative system: bicameral Parliament (Sansad) consists of the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) and the People's Assembly (Lok Sabha)

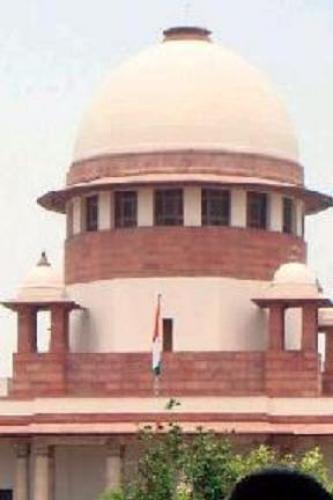

judicial system: Supreme Court, judges are appointed by the president and remain in office until they reach the age of 65

religion: 80% Hindu; 11% Muslim; 2% Christian; 2% Sikh; Buddhist and other minorities

death row: 404 (as of March 31, 2013)

year of last executions: 21-11-2012

death sentences: 75

executions: 1

international treaties on human rights and the death penalty:International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (signed only)

situation:

The death penalty is provided for by the Penal Code and by Art. 21 of the Constitution which states: "No person may be deprived of their life or personal freedom except in cases established by law."

Death-qualifiable offences are conspiracy against the Indian Government; desertion or attempted desertion; murder or attempted murder; inducement to suicide of a minor or a mentally-retarded person. Section 303 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) prescribes the death penalty alone with no alternative in cases where a convict serving a life sentence commits murder. The court under this section cannot exercise its discretion and award a lesser sentence.

The death penalty is also applicable under the military statutes (Army Act, 1950, Air Force Act, 1950, Navy Act, 1956).

In 1987 India passed the Commission of Sati Prevention Act which prescribes the death penalty for people found guilty of instigating sati, or sacrificial suicide by the widow, in cases where the suicide is successful.

The December 1988 Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Amendment Act makes a second conviction for drug-trafficking a capital offence. On 16 June 2011, the Bombay High Court, one of the oldest and chartered High Courts in India, struck down the mandatory death penalty for drug offences. Announcing the order via video conferencing, a division bench of Justices A.M Khanwilkar and A.P Bhangale declared Section 31A of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS Act), that imposes a mandatory death sentence for a subsequent conviction for drug trafficking, ‘unconstitutional’. The Court, however, refrained from striking down the law, preferring to read it down instead. Consequently, the sentencing Court will have the option, and not obligation, to impose capital punishment on a person convicted a second time for drugs in quantities specified under Section 31A. It should be noted however that only on 28 January 2012, in the first ever case of capital punishment in a drug crime, a special Narcotics court in Chandigarh, awarded death penalty to a person while sentencing an African national to 15-years of Rigorous Imprisonment (RI).

Special courts applying the Terrorist Affected Areas Special Courts Act, 1984, and the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), 2002, were empowered to impose the death sentence for terrorism. The latter law, which had broadened the scope of the death penalty, when the Hindu nationalist BJP was in government and after an attack on the Indian parliament in December 2001, was considered as contrary to human and political rights by the government, dominated by the Party of Congress of Sonia Gandhi, after achieving victory in the elections of May 2004. This law was repealed by the Parliament on December 9, 2004 by voice vote amidst a walkout by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the main Opposition party. Under the same considerations of national security, the POTA was replaced by the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Bill, which amended the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 to cover terrorism. The Bill provides that people convicted of terrorism will be punishable by the death penalty or life imprisonment and a fine for any act which results in loss of life. Under the Bill, anyone threatening unity, integrity, security or sovereignty or striking terror in the people in India or in any foreign Country by using bombs, dynamite or other explosive or inflammable substances or firearms or other lethal weapons causing or likely to cause death is liable for punishment.

The fight against terrorism was behind a bilateral extradition treaty between India and France signed in January 2003. The treaty involved Indian assurances that criminals would not be given capital punishment upon extradition from France.

On 21 December 2011, in an effort to secure the strategically important oil pipelines from acts of terrorism like sabotage, Parliament gave assent to death penalty for such crimes by amending the Petroleum and Minerals Pipelines (Acquisition of Right of User in Land) Amendment, Bill 2011. The punishment “may extend to imprisonment for life or death” in case the act of sabotage is dangerous and is likely to cause death of any other person, the amendment Bill states. Prior to the amendment, the Act provided for a jail term of one to three years’ for acts of sabotage and pilferage.

On 1 February 2012, the Supreme Court held that Section 27(3) of the Arms Act, 1959 that provides for “mandatory death penalty” in case of death being caused by use of prohibited arms is ultra vires (beyond the powers) of the constitution and declared it void. The provision of death sentence was inserted in Section 27 of the Arms Act by amending it in 1988 in the wake of terrorist and anti-national activities in Punjab. Prior to the amendment, the maximum sentence under this section was seven years or fine or both.

On April 5, 2013, Indian President Pranab Mukherjee has given his assent to the anti-rape bill which details life prison terms and even death sentences for rape convicts, as well as stringent punishments for such offenses as acid attacks, stalking and voyeurism. Mukherjee accorded his assent to the Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill-2013 on Tuesday (April 2), brought against the backdrop of the country-wide outrage over the Delhi gang rape, and it will now be called the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, an official release said Wednesday (April 3). The law, passed by the Lok Sabha (Lower House) on March 19 and by the Rajya Sabha (Upper House) on March 21, has replaced an ordinance promulgated on Feb. 3. It amends various sections of the Indian Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Indian Evidence Act and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act. With an aim of providing a strong deterrent against crimes such as rape, the new law states that an offender can be sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for a term which can't be less than 20 years, but which may extend to life, meaning imprisonment for the remainder of the convict's life and with a fine. It has provisions for handing out death sentence to offenders who may have been convicted previously for such crimes. The law, for the first time, defines stalking and voyeurism as nonbailable offences if repeated for a second time. Perpetrators of acid attacks will attract a 10-year jail sentence.

It also defines acid attacks as a crime, as well as grants a victim the right to self-defense. It also has provisions for imposing a minimum 10-year jail term for perpetrators of such acts. The law has fixed the age for consensual sex at 18 years. New sections to prevent stalking and voyeurism were introduced following a strong demand from women's organizations.

On 3 February 2013, President Pranab Mukherjee gave his assent to the anti-rape law ordinance after cabinet ministers recommended changes to impose harsher punishments for rapists, including the death penalty. "The President has given his assent to the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance 2013," a Home Ministry spokesperson said. "It comes into effect immediately but it will also be tabled before the parliament," added a senior officer in the president's office. On 2 February, a government-appointed panel of jurists – Justice JS Verma Committee – and the cabinet had recommended tougher laws, as a response to the gang-rape tragedy that took place in New Delhi. There were vociferous demands for death penalty, but the Verma Committee excluded it. The committee had proposed to replace the word 'rape' with 'sexual assault', which will also help to expand the definition of all types of sexual crimes against women. It also proposed enhanced punishment for other crimes against women like stalking, voyeurism, acid attacks, indecent gestures like words and inappropriate touch and brings into its ambit 'marital rape'. In the existing law, a rapist faces a term of seven to 10 years. Under the changes, the minimum sentence for gang-rape, rape of a minor, rape by policemen or a person in authority will be doubled to 20 years from 10 and can be extended to life without parole. The government went beyond the committee's recommendations and introduced death penalty for the accused if the victim died or fell into vegetative state. Repeat offenders of sexual assault by gang will be punished by imprisonment for life or with death.

On 10 February 2010, the Supreme Court has made it clear that having already served a long prison sentence and poor socio-economic conditions are extenuating circumstances that can lead to a sentence be commuted to life in the capital.

Death sentences must be confirmed by the Supreme Court, which itself ruled on 9 May 1980, in the landmark judgment “Bachan Singh v State of Punjab” that the death sentence as a punishment should be given only in the “rarest of rare” cases. On 11 August 2008, in the case of Murli Manohar Mishra alias Swami Shraddhananda, the Indian Supreme Court ruled that in order to minimize the use of death penalty, it has the power to fix tenure of life imprisonment while substituting it for death sentence. The high court in its judgment noted, “further formalization of a special category of sentence, though for an extremely few number of cases, shall have the great advantage of having the death penalty on the statute book but to actually use it as little as possible, really in the rarest of the rare cases.”

On 18 August 2009, the Supreme Court, in a case in which the high court awarded a life sentence to four members of a gang responsible for killing three “Shiv Sena” workers in Mumbai in March 1999, expressed its concern by the varying interpretation of the “rarest of rare case” guidelines laid down in Bachan Singh judgment and said the time had come for an attempt towards deciphering a common view on this to usher in “some objectivity to the precedent on death penalty which is crumbling down under the weight of disparate interpretations.” On 20 November 2012, in the case of Sangeet & Anr versus State of Haryana, the Supreme Court has said its Constitution bench's landmark judgement of 1980 on criterion for imposing death penalty needs a "fresh look" as there has been "no uniformity" in following its principles on what constitutes "the rarest of rare" cases.

The Indian legislative system provides for different levels of appeal, and death sentences are frequently commuted to life imprisonment upon appeal. India keeps no official statistics on the number of death sentences and executions, nor on the number of people on death row. The President also has the power to issue pardons. Article 72 of the Constitution empowers the President to pardon, grant reprieve or suspend, remit, commute sentence of a person convicted for any offence. The President is guided and advised by the home minister and the council of ministers in his decision. There is no timeframe in which the President has to make the decision which is subject to judicial review after the India’s Supreme Court decision of October 11, 2006 that clipped the president’s power to pardon convicts on death row. Powers to grant pardon were subject to judicial review if there was an “extraneous consideration in the exercise of that power,” the court ruled.

President Pratibha Devisingh Patil, who ended his term in June 2012, was the most “merciful” of all presidents during the last three decades as she commuted death sentences of 38 petitioners to life imprisonment during her tenure. During her mandate, she rejected 5 petitions. The move by Patil did not see any protest from government quarters. The Indian media, however, has generally been critical of her record on the issue, questioning why clemency was deemed appropriate in some cases involving murder, rape and child abduction.

In 2012, India resumed executions since 14 August 2004, when Dhananjoy Chatterjee was hanged for raping and killing a girl.

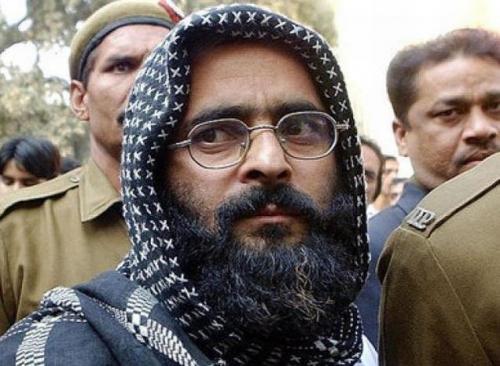

On 21 November 2012, Mohammad Ajmal Kasab, a 25 year old Pakistan national, the lone survivor of a militant squad that killed 166 people in a rampage through the financial capital Mumbai in November 2008, was hanged in secrecy at 7:30 a.m. at Yerwada Jail in Pune in Pune, a city near Mumbai, after Indian President Pranab Mukherjee rejected his plea for mercy. He was buried inside the prison where he was hanged, officials said.

Indian authorities faced public pressure to quickly execute Kasab, and the government fast-tracked the appeal and execution process, which often can take years, or in some cases, decades.

The National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) statistics reveal that 1,460 persons were sentenced to death by Indian courts between 2001 and 2011, an average of 146 death sentences every year. The NCRB stats also reveal that in the same period, various higher courts commuted death sentences of 4,321 convicts to life imprisonment. In spite of so many death sentences passed by Indian courts, nearly 99 per cent convicts never face the gallows. In fact, India has executed only 4 people in the last 20 years: “Auto” Shankar (in 1995), Dhananjoy Chatterjee (2004), Ajmal Kasab (2012) and Afzal Guru (2013). The last reported executions prior to the August 2004 one had taken place in 1995, when five people were hanged. A well-remembered execution was that of Nathuram Godse, the man condemned for assassinating India’s founding father Mahatma Gandhi. It took him 15 minutes to die as he dangled from the rope. A similar fate, in 1989, awaited Kehar Singh and Satwant Singh, convicted of the 1985 assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

Mahatma Gandhi had been a firm opponent of the death penalty. “I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life because he alone gives it.

At least 78 new death sentences were imposed in 2012, according to Amnesty International.

However, in the aftermath of the Delhi gang-rape in December 2012, the number of death sentences pronounced by the lower courts has grown remarkably. Courts in western Odisha have sentenced at least five persons to death for rape and murder. In the last nine months, courts in Bihar have sentenced 4 to death; Jharkhand 2, Punjab 3, and Madhya Pradesh 12.

As of 31 March 2013, there were 404 convicts on death row in various prisons across the country.

On December 20, 2012, India voted against the Resolution on a Moratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty at the UN General Assembly.