government: Traditional monarchy

state of civil and political rights: Not free

constitution: governed according to Shari'a (Islamic law); the Basic Law that articulates the government's rights and responsibilities was introduced in 1992

legal system: based on Sharia law; several secular codes have been introduced

legislative system: a consultative council (90 members and a chairman appointed by the monarch for four-year terms)

judicial system: Supreme Council of Justice

religion: Muslim 100%

death row: more than 100 (Sources: AI, 10/06/2011)

year of last executions: 0-0-0

death sentences: 44

executions: 88

international treaties on human rights and the death penalty:Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

situation:

Saudi Arabia’s legislation is based on both Sharia principles and

customary law, and the Koran and the Sunna make up the Kingdom’s Constitution.

Saudi Arabia is the Islamic country that most strictly interprets Sharia

law. It prescribes the death penalty for murder, apostasy, rape, drug trafficking,

witchcraft, adultery, consensual sexual relations between adults of same sex,

apostasy, terrorism, treason, espionage and military offences.

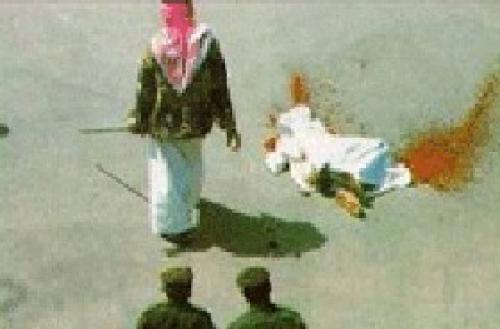

Beheading as a means of carrying out executions is exclusive to Saudi

Arabia.

Saudi Arabia has one of the highest execution rates in the world, both in terms of number of people

killed and in relation to its population. Between 1980 and 2002, approximately

1,500 people were put to death in the country. The record number of beheadings

in one year in Saudi Arabia was 191 in 1995.

Many of the announced Saudi executions were for murder and rape, but a wide

range of non-violent crimes also resulted in decapitation. Among the lesser

offences that led to executions were apostasy, witchcraft, sexual practices

considered offences (adultery, sodomy, homosexuality) and crimes involving both

hard and soft drugs.

Dozens of people are arrested each year on charges like witchcraft, recourse to

supernatural beings, black magic and fortune telling. These practices are

considered polytheistic and severely punished according to Sharia law.

The crime of “sorcery” is not defined in Saudi Arabian law but it has been used

to punish people for the legitimate exercise of their human rights, including

their right to freedom of expression. In March 2012, Saudi Arabia decided to

bolster its religious police unit specialized in arresting magicians within an

ongoing war on sorcery which is punishable by execution in the Gulf Kingdom.

The Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, the

influential law enforcement authority in Saudi Arabia, announced that it had

created a “field unit” charged with fighting sorcerers, who it described as

“key causers of religious and social instability in the country.” The new unit,

headed by Sheikh Adel Al Muqbil, a prominent scholar in the Kingdom, “has been

given orders to immediately arrest sorcerers and charlatans and refer them to

the specialized authorities to apply God’s punishment on them and end their

harmful deeds against Muslims,” the Commission said. The Commission has not

specified witchcraft offences in the Kingdom but there have been reports of

cases involving all forms of black magic, including dowsing, exorcism, money

cloning, fortune tellers, healers, bone-setters, makers of potions, herbalists,

palmists, animal callers, alchemists, psychics, and empathy.

In November 2014, the Saudi Arabian government decided to

impose the death sentence on anyone who attempts to import "all

publications that have a prejudice to any other religious beliefs other than

Islam." In other words, anyone who attempts to bring Bibles or Gospel

literature into the country will have all materials confiscated and be

imprisoned and sentenced to death.

It was reported on September 27, 2005, that Saudi Arabia redefined its drug trafficking laws, giving discretionary powers

to judges and allowing them to hand down jail sentences instead of awarding the

death penalty. The Saudi Anti-Drug and Mental Effects Regulation stipulated the

death penalty for drug traffickers, manufacturers and recipients of any

narcotic substances. Judges could now exercise discretion to reduce the

sentence to imprisonment for a maximum of 15 years, sessions of 50 lashes, and

a minimum fine of 100,000 Saudi riyals [more than 26,000 US dollars].

About two thirds of those executed in Saudi Arabia are foreigners. Saudi

justice is especially harsh in its treatment of foreign workers, particularly

those from poorer countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, who make up

about a quarter of the Saudi population. Migrant workers are vulnerable to

abuse from their employers as well as from the authorities. If arrested,

foreign nationals may be tricked or coerced into signing a confession in

Arabic, which they may not understand. Migrant workers are frequently tortured

and ill-treated and more likely than Saudis to be executed or punished by

flogging or amputation.

Foreigners condemned to death in Saudi Arabia are typically unaware of their

sentences and have no advance notice of their date of execution. In most cases,

the condemned people do not even know that their trials has been concluded. The

executed do not know what is about to happen to them until the very last

moment. A large number of police come into the cell and ask for the person by

name. Sometimes people are forcibly dragged out.

Human rights organizations maintain that Saudi Arabia often fails to give

defendants fair trials.

Defendants are frequently denied legal assistance before their trials, and

legal representation when they appear in court. In October 2002, Saudi Arabia

allowed access to a UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of the judiciary

for the first time.

On September 12, 2005, Saudi Arabia decided to create a Governing Commission

for Human Rights. According to an official communication, the Commission has

the duty to “protect and strengthen human rights, defend their awareness and

ensure the respect of human rights while following Islamic law.” The decision

to create the commission shortly followed the ascension to the throne of King

Abdullah in August after the death of King Fahd. The creation of a Governmental

body on human rights had been scheduled in previous years.

Saudi Arabia does not have a penal code and judges pass verdicts based on their own

interpretation of Sharia law. In particular, the manner of dealing with

minors, who have been sentenced to flogging or even to death, is cruel and

contradicts the principles of the rule of law and the minimum standards

established by international law. Saudi Arabia ratified the UN Convention on

the Rights of the Child in 1996 and considers it to be a valid source of domestic law.

The treaty prohibits the death penalty and life imprisonment

without parole as punishments for those under the age of 18 at the time of

their crime. However, the Saudi authorities do not seem to take their assumed

responsibilities on human rights through adherence to international treaties

very seriously, because there is a huge divergence between the commitments made

by Saudi Arabia for human rights and its daily reality. Furthermore, the Sharia law of the Kingdom never imposes the

death penalty on persons that have not reached the age of adulthood, and on the

basis of the Regulations of Detention and the Regulations of Juvenile Detention

Centres of A.H. 1395 (1975), that is defined as anyone under the age of 18.

However, a judge could issue a death penalty against the accused if he/she felt

that the offender had reached maturity, regardless of their actual age at the

time of the crime. At least 126 individuals were on death row in Saudi

Arabia for crimes they were found to have committed before age 18, the Saudi

online news station alarabiya.net reported in November 2005, citing government

sources. Human Rights Watch had received reliable reports of children sentenced

to death for crimes committed when they were as young as 13. In 2011, Saudi

Arabia beheaded one person who was officially described as a “juvenile”. In

2009, Saudi Arabia executed two people who were under the age of 18 at the time

of the alleged crimes, while in 2007 there were three of such executions. In 2008 and 2010, no executions of juvenile

offenders were reported.

In Saudi Arabia, acts of terrorism – such as hijacking planes, terrorising

innocent people and shedding blood – amount to “corruption on earth”, a

charge that can carry the death penalty even when the offences do not result in

lethal consequences. The authorities set up specialised courts in 2011 to try

Saudis and foreigners accused of belonging to Al-Qaeda or involvement in

a spate of deadly attacks in the kingdom from 2003-2006. In 2014, at least 59 suspected terrorists were sentenced to death in Saudi Arabia.

On 12 January 2010, Saudi Arabia’s Shura Council passed legislation amending the

Criminal Procedure Law so that death sentences can only be issued if approved

unanimously by all judges in the case. The law stated previously that a

majority vote from the judges is adequate to pass the death sentence. The

amendment also states that lower court verdicts dealing with the severing of

hands or similar punishments must be unanimous, and will not be carried out

without a verdict from the Supreme Court. An overwhelming majority of 92

members voted in favour of the new amendment, while a few members opposed it.

On 14 October 2012, the Shura Council reiterated that a death sentence

issued on the basis of a judge’s discretionary power becomes final only if the

verdict is unanimous. “The court’s endorsement of the death penalty on Tazir

(a judge’s discretion in situations where no religious punishment is

prescribed) should not be made final unless it is by unanimous agreement,” the

council stipulated while discussing recommendations on criminal regulations

made by the Committee for Islamic & Governmental Affairs. The Council voted

down the committee’s recommendation that the implementation of Tazir for

death punishment can be implemented even if the decision is made without

unanimity.

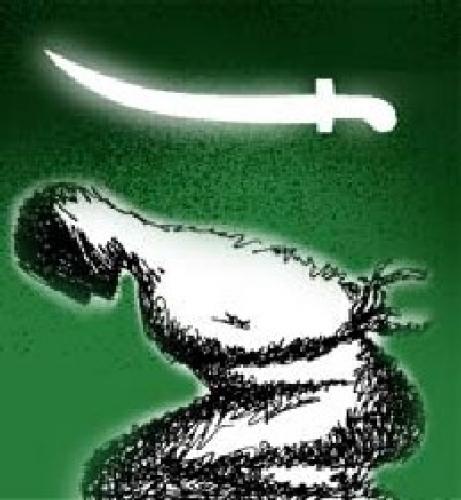

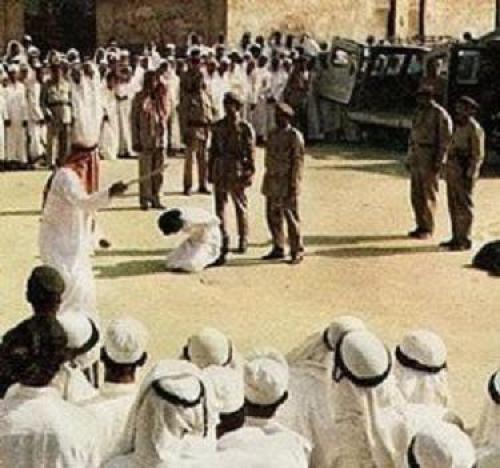

Executions take place in public in the conservative kingdom, and by beheading. They are public domain only

once they are carried out, while family members, lawyers and the condemned

themselves are kept in the dark. The executions are announced by the Minister

of the Interior generally and, usually, filmed by the official Saudi news agency

SPA. State-ordered beheadings are performed in courtyards

outside crowded mosques in major cities after weekly Friday prayer services. A

condemned convict is brought into the courtyard, hands tied, and forced to bow

before an executioner, who swings a huge sword amid cries from onlookers of

"Allahu Akbar!"- Arabic for "God is great." Sometimes, beheading is followed by the public display of the bodies of

the executed. The typical procedure of beheading provides for the executioner

to re-fix the beheaded head onto the body of the executed, so that it may be

hung, generally, for about two hours, from the window or balcony of a mosque or

hung upon a pole, during midday prayers. The pole is sometimes shaped in the

form of a cross, hence the use of the term “crucifixion”. The bodies of the

executed are displayed only on specific orders from the tribunal, when the

crime committed is considered particularly heinous.

In March 2013, Saudi Arabia has authorised regional governors to approve

executions by firing squad as an alternative to public beheading, the customary

method of capital punishment in the kingdom, the Arab News reported on March 11. On March 10, another

newspaper, Al Youm, said the reason for the change was a shortage of

qualified swordsmen. Al Youm reported a circular by the Government’s

bureau of investigation and prosecution as saying the use of firing squads was

being considered because some swordsmen had to travel long distances sometimes

to get to the place of executions, making them sometimes late. The circular

stated that death by firing squad was not a breach of Sharia law. Al

Youm said a firing squad had been used to carry out the death sentence

against a convicted female in a case in Ha’il in north-western Saudi Arabia a

few years ago.

On 13 March 2013, a senior cleric gave his seal of approval for

execution by firing squad, as long as it is as quick or faster than the

traditional method of beheading, it was reported. Sheikh Ali Al-Hakami, member

of the Senior Board of Ulema, was quoted by English language Saudi Gazette

as saying that death by firing squad could be permissible according to Sharia,

as long as the process is painless. “That’s why beheading by sword is the best

way to achieve the purpose of punishment in Islam because it does not cause any

torture,” Al-Hakami said. Al-Hakami added that religious scholars in the Gulf’s

most populous country should also investigate the possibility of using other

methods, such as electric chair, hanging and lethal injections, to find out if

they also comply with Sharia.

The pardon by the victims’ families has to be documented in a court of justice.

Three judges check the information and the form of the granted pardon before

they allow the procedure to go ahead. They also check whether the families’ pardoning

of the prisoners has any special conditions or requirements. In Saudi Arabia,

numerous cases involving “blood money” were resolved positively thanks to the

Saudi Reconciliation Committee (SRC), a nation-wide organization that secures

pardons for death row prisoners and helps settle lengthy inter-family and

tribal disputes through mediation. The SRC, whose executive chairman is Nasser

Bin Mesfir Al-Zahrani, is credited with saving the lives of hundreds of people

sentenced to death since its inception in 2008. Its mission is to prevent

haggling by the families of the murder victims over blood money Diya. In

recent years, there has been growing concern in various parts of the Moslem

world over the growing trend of exorbitant blood money demands, which many

say are fuelled by greed and tribal rivalries. Officials, clerics and writers

have spoken out against the excessive requests, saying an ancient Islamic

practice meant to financially support those who lose loved ones has been

corrupted. In September 2011, Saudi Arabia decided to

triple Diya, the money paid by a killer to the victim’s relatives under

Islamic law, but kept the sum for female victims at half that for male victims.

The Kingdom’s supreme judicial authority raised Diya to 300,000 Riyals

(80,000 USD) from 100,000 Riyals (26,666 USD) in accidental death and 400,000

Riyals (106,666 USD) in premeditated murder. Blood money values have been

static for the last 29 years. The Supreme Council of Scholars had called for

reviewing Diya in light of the increasing prices of camels, which were

used as blood money in the old Islamic age. According to Sharia rules,

the heirs of a murdered person should be compensated with 100 camels.

In 2002, Hands Off Cain counted 49 executions, including at least one woman. 82

executions, including 2 women, were carried out in 2001. At least 52 people

were beheaded in the country in 2003, including one woman. Thirty eight

executions took place in 2004, the lowest number in recent years, however that

figure has already been overtaken with at least 90 executions in 2005. In 2006,

Hands Off Cain counted 39 executions, 166 in 2007, at least 102 in 2008, 69 in

2009, 27 in 2010 and 81 in 2011. In 2012, Saudi Arabia beheaded at least 84

people, 43 Saudis and 41 foreigners, according to a Hands Off Cain tally based

on media reports. A majority of those who were executed were convicted of

murder (43), followed by drug-related offences (37), armed robbery (2), sorcery

(1), and sodomy (1). In 2013, Saudi Arabia beheaded at

least 78 people, 43 Saudis and 35 foreigners. The beheading tally in 2014

reached its highest level in the past five years. Saudi Arabia executed at

least 87 people, according to a Hands off Cain tally based on media reports.

A majority of those who were executed were convicted of murder, followed by

drug-related offences, armed robbery, and incest. In 2015 (as of 26 February),

the kingdom executed at least 34 people, according to an Agence France

Presse tally based on official figures.

On 21 October 2013, Saudi Arabia was reviewed under the Universal Periodic Review of

the UN Human Rights Council. The Government rejected all the recommendations

dealing with the abolition of the death penalty, including recommendation to establish

alternative punishments to the death penalty and suspend its application for

less serious offences and for people who were minors at the time of the crimes,

in the perspective of a moratorium on executions. In response to comments and

questions, Saudi Arabia noted that the death penalty is imposed only for the

most serious crimes and strict procedures are applied to safeguard human rights

when the death penalty is imposed insofar as the judgments are reviewed by 13

judges at the three levels of jurisdiction, in a manner consistent with

international standards.

On 11 June 2014, Saudi Arabia’s Justice Minister defended tough Sharia

punishments such as beheading, cutting off hands and lashing, claiming they

“cannot be changed” because they are enshrined in Islamic law. “These

punishments are based on divine religious texts and we cannot change them,”

Mohammed Al Eissa said during a speech in Washington. The minister said Islamic

law had helped to reduce crime in the conservative kingdom. “Islam sympathises

with the victim, not the criminal,” Al Eissa said. Speaking to American

lawyers, legal consultants and academics, Al Eissa criticised international

human rights groups that call for changes to the kingdom’s judiciary, claiming

they made “big mistakes” because they misunderstood the country and Islam. “Any

attack on the judiciary will be considered an attack on the kingdom’s

sovereignty,” he said.

On 9 September 2014, U.N. independent experts called on Saudi Arabia to implement an immediate moratorium

on the use of the death penalty. "Despite several calls by human rights

bodies, Saudi Arabia continues to execute individuals with appalling regularity

and in flagrant disregard of international law standards," said Christof

Heyns, the U.N. special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary

executions. "The trials are by all accounts grossly unfair. Defendants are

often not allowed a lawyer and death sentences were imposed following

confessions obtained under torture."

On December 18, 2014, Saudi Arabia voted against the Resolution on a Moratorium

on the Use of the Death Penalty at the UN General Assembly. oratorium on the Use of the Death Penalty at the UN General Assembly.