03 January 2011 :

SYNTHESIS OF THE 2010 REPORTTHE SITUATION TODAY

The worldwide trend towards abolition, underway for more than ten years, was again confirmed in 2009 and the first six months of 2010.

There are currently 154 countries and territories that, to different extents, have decided to renounce the death penalty. Of these: 96 are totally abolitionist; 8 are abolitionist for ordinary crimes; 6 have a moratorium on executions in place and 44 are de facto abolitionist (i.e. countries that have not carried out any executions for at least 10 years or countries which have binding obligations not to use the death penalty).

Countries retaining the death penalty worldwide are down to 43, compared to the 48 retentionists in 2008, 49 in 2007, 51 in 2006 and 54 in 2005.

In 2009, the number of countries resorting to the death penalty was 18, a considerable decrease compared to 2008 and 2007 when there were 26.

The gradual abandonment of the death penalty is also evident in the declining use of capital punishment by countries that still maintain death as the maximum penalty for criminal acts. In 2009, at least 5,679 executions were carried out, down from a minimum of 5,735 in 2008 and a minimum of 5,851 in 2007.

In 2009 and in the first six months of 2010, there were no executions in 9 countries where executions were carried out in 2008: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Belarus (which went on to carry out two in the first months of 2010), United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, Mongolia (which has gone on to declare a moratorium on executions), Pakistan, Saint Kitts & Nevis and Somalia.

On the other hand, 3 countries resumed executions: Thailand (2) in 2009, after stopping in 2008; Taiwan (4) and Palestinian National Authority (5) in 2010, after five years of suspension.

Of the 43 countries worldwide that retain the death penalty, 36 are dictatorial, authoritarian or illiberal States. Fifteen of these countries were responsible for approximately 5,619 executions, about 99% of the world total in 2009. It points to the fact that the fight against the death penalty entails, beyond the stopping of executions, a battle for democracy, for the respect of the rule of law and for political rights and civil liberties.

The terrible podium of the world’s top executioners is taken by three authoritarian States in 2009: China, Iran and Iraq.

Of the 43 retentionists, only 7 countries are considered liberal democracies. This definition, as used here, takes into account the country’s political system and its respect towards human rights, civil and political liberties, free market practices and the rule of law.

There were 3 liberal democracies that carried out executions in 2009, and they accounted for 60 executions between them, about 1% of the world tally. These were: The United States (37), Japan (7) and Botswana (1). In 2008 there were 6 (with Indonesia, Mongolia and Saint Kitts and Nevis) and they carried out 65 executions.

Once again, Asia tops the standings as the region where the vast majority of executions are carried out. Taking the estimated number of executions in China to be about 5,000 (more or less equal to the number in 2008 but diminished in respect to preceding years), the total for 2009 corresponds to a minimum of 5,608 executions (98.7%), down from a minimum of 5,674 in 2008.

In the Americas, the United States of America was the only country to carry out executions (52) in 2009.

In Africa, in 2009, the death penalty was carried out in only 4 countries – Botswana (1), Egypt (at least 5), Libya (at least 4) and Sudan (at least 9) – where there were at least 19 executions as in 2008 and compared to 26 in 2007 and 87 in 2006 on the entire continent.

In September 2009, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights organized a sub-regional conference in Kigali, Rwanda, to discuss the abolition of the death penalty in central, eastern and southern Africa. Fifty participants representing different African Union member states and national human rights commissions agreed to support the abolition of the death penalty by putting emphasis on a formal moratorium that can be adapted on the basis that governments can be held accountable. The participants also recommended the drafting of a protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the abolition of the death penalty in Africa. “We urge all the AU member countries which have not yet done so to subscribe to Human Rights Instruments that prohibit the death penalty, namely the 2nd Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights and the Rome Statute and align national legislation accordingly,” their resolution document says in part.

Between April 12-15, 2010, the death penalty working group of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights organized a second regional meeting in Cotonou, Benin. The conference focused on North- and West-African countries and around 50 people from 15 countries in the region came to take part in the debates. Plenary sessions and workshops targeted the death penalty in Africa and the means to achieve abolition.

A continental conference involving experts and officials from African Union member states will follow the Kigali and Cotonou regional meetings. African Commissioner Sylvie Kayitesi, who chairs the working group, is planning to use that opportunity to present African heads of State and government with a draft of an additional protocol on the death penalty to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Such a move would give Africa a chance to adopt a binding instrument calling for the abolition of the death penalty.

In Europe, the only blemish on an otherwise completely death penalty-free zone continues to be Belarus. In 2009 there were no executions, but in March of 2010 two men were put to death for homicide. At least 4 executions were held in 2008. There was at least 1 in 2007 and, according to OSCE records, there were at least 3 executions in 2006 and 4 in 2005.

A resolution on a moratorium on the death penalty and towards its abolition was adopted during the annual session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), held between June 29 and July 3, 2009 in Vilnius, Lithuania. The resolution specifically urges OSCE participating states Belarus and USA to adopt an immediate moratorium on executions, and calls on Kazakhstan and Latvia to amend provisions in their national legislation that still allow for the imposition of the death penalty for certain crimes under exceptional circumstances.

After 2008, when 3 countries became total or de facto abolitionist, another 6 joined the list in 2009 and the first six months of 2010.

In April 2009, Burundi adopted a new penal code abolishing the death penalty. In June 2009, Togo’s parliament voted unanimously to abolish the death penalty. In July 2009, the President of Kazakhstan supported a law that limited the death penalty exclusively for crimes of terrorism causing death and for especially grievous crimes committed in time of war. As of July 2009, Trinidad & Tobago has gone more than ten years without practicing the death penalty, establishing itself as de facto abolitionist country. As of January 2010, The Bahamas have gone more than ten years without practicing the death penalty, establishing themselves as de facto abolitionist country. In January 2010, Mongolia’s President announced a moratorium on the death penalty.

In 2009 and in the first six months of 2010, significant political and legislative steps towards abolition or at least positive signs, such as collective commutations of capital punishment, have been seen in numerous countries.

In April 2009, the Justice Minister said the death penalty will be abolished in Jordan for all crimes except premeditated murder. In June 2009, a conference in the Democratic Republic of Congo concluded with the National Assembly President and Senate President announcing the start of the legislative process to abolish the death penalty in Congo. In June 2009, Vietnam voted in favor of abolishing the death penalty for eight crimes. In August 2009, the Justice Ministry in Lebanon launched a nationwide campaign to rally public support for the abolition of the death penalty. In September 2009, the government of South Korea agreed to the non-application of the death penalty, as requested by the Council of Europe. In November 2009, the government of Benin submitted a government bill to the National Assembly concerning the constitutional abolition of the death penalty. In April 2010, Djibouti, already abolitionist for all crimes, approved an amendment that introduces the abolition of the death penalty in its Constitution.

In 2009, for the first time in the country’s history, there were no executions in Pakistan.

On January 7, 2009, on his last day in office as President of Ghana, John Kufuor pardoned more than 500 prisoners. In January 2009, Uganda’s Supreme Court ruled that death sentences be commuted to life imprisonment after three years in jail. In January 2009, the President of Zambia pardoned and commuted the sentences of 53 prisoners on death row. In July 2009, King Mohammed VI of Morocco amnestied about 24,000 prisoners to mark the 10th anniversary of his coronation – many people currently on death row will have their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. In August 2009, President Mwai Kibaki of Kenya announced more than 4,000 death row inmates would all have their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. In August 2009, Lagos State Governor in Nigeria granted an amnesty to 3 prisoners sentenced to death and pardoned a further 37 death row inmates. In November 2009, the President of Tanzania commuted 75 death sentences to life imprisonment.

In the United States, the State of New Mexico abolished the death penalty on March 18, 2009, becoming only the second U.S. State in over forty years to do so, following New Jersey’s abolition of capital punishment on December 13, 2007. The State of Connecticut came close to abolishing the death penalty with both the State Senate and House of Representatives voting for abolition only to have the legislation vetoed by State Governor M. Jodi Rell on June 5, 2009.

Negative developments were topped by the resumption of executions by Thailand in August 2009, after about six years of de facto moratorium.

In April 2010, in Palestine the Hamas government in Gaza took it upon itself to resume executions after a de facto moratorium that had lasted five years. At the end of April 2010, Taiwan also resumed executions after five years of suspension.

The information contained in this report is the result of daily monitoring of news and developments concerning the death penalty worldwide. It offers a comprehensive overview of relevant events that took place in 2009 and in the first six months of 2010. All information contained in this report, including sources, dates of reports and more is available on Hands Off Cain’s online death penalty news database at www.handsoffcain.info

TOP EXECUTIONERS FOR 2009: CHINA, IRAN AND IRAQ

Of the 43 countries worldwide that retain the death penalty, 36 are dictatorial, authoritarian or illiberal States. Fifteen of these countries were responsible for approximately 5,619 executions, about 99% of the world total in 2009.

China alone carried out about 5,000, or 88%, of the world total of executions; Iran put at least 402 people to death and Iraq at least 77; Saudi Arabia, at least 69; Yemen, at least 30; Sudan and Vietnam, at least 9; Syria, at least 8; Egypt, at least 5; Libya, at least 4; Bangladesh, 3; Thailand, 2; North Korea, at least 1; Singapore, 1. It is possible that executions were carried out in Malaysia, although none were officially reported.

Many of these countries do not issue official statistics on the practice of the death penalty, therefore the number of executions may, in fact, be much higher.

In some countries, such as China and Vietnam, the death penalty is considered a State secret and reports of executions carried by local media or independent sources – upon which the execution totals are mainly based – in fact represent only a fraction of the total of executions carried out nationwide every year.

The same is applicable for Belarus, where news of executions filters mainly through relatives or international organizations long after the fact.

In Iran, that carries out executions regularly without classifying the death penalty as a State secret, the main sources of information on executions are reports selected by the regime and carried by State media. These reports do not carry news of all executions, as evidenced by information occasionally divulged by individual citizens or by political opposition groups.

Absolute secrecy governs executions in some countries, such as North Korea, Malaysia and Syria, where news of executions does not even filter through to the local media.

Secret executions are being carried out in Iraq in the prisons run by Nouri al-Maliki’s government as well.

Other States, like Saudi Arabia, Botswana, Egypt, Japan and Singapore divulge news of executions after they have taken place with relatives, lawyers and the condemned people themselves being kept in the dark before the actual executions take place.

This is the prevalent situation worldwide concerning the practice of the death penalty. It points to the fact that the fight against the death penalty entails, beyond the stopping of executions, a battle for transparency of information concerning capital punishment, for democracy, for respect of the rule of law and for political rights and civil liberties.

The terrible podium of the world’s top executioners is occupied by three authoritarian States in 2009: China, Iran and Iraq.

China: Officially the World’s Record-holder for Executions (Despite a Significant Reduction)

Although the death penalty remains a State secret in China, some news in recent years, including declarations from official sources, suggest that the use of the death penalty may have diminished as much as 30% compared to preceding years.

A major turnabout came after the introduction of a legal reform on January 1, 2007, which requires that every capital sentence handed down in China by an inferior court be reviewed by the Supreme Court.

The China Daily newspaper reported that the Supreme People’s Court overturned 15 per cent of death sentences handed down in 2007 and 10 per cent in 2008.

According to The Dui Hua Foundation’s estimate, the number of prisoners executed annually may have fallen by as much as half from the 10,000 cited by a National People’s Congress delegate in 2004. In any event, statistics and percentages are of little value as all aspects of capital punishment remain a State secret including the actual number of death sentences and executions.

The Dui Hua Foundation, a San Francisco-based group that works on behalf of political prisoners and monitors Chinese prisons, estimates that “about” 5,000 executions were carried in China in 2009, while the number of executions in 2008 – according to the Foundation – “exceeded 5,000 and may have been as high as 7,000.” According to the Foundation, run by business executive-turned-human-rights advocate John Kamm – who still maintains good relations with government officials – about 6,000 people were executed in 2007, a 25 to 30 percent drop from 2006, in which estimates reported at least 7,500 executions.

Not even Amnesty International knows the exact number of executions carried out in 2009. However, according to Amnesty, “evidence from previous years and current sources indicates that the figure is in the thousands.” Amnesty International had reported at least 1,718 executions in 2008, though the same organization warned that the real number could be much higher.

On July 29, 2009, Zhang Jun, Vice-President of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), said China was to reduce the number of people it executes to “an extremely small number.” The top court official said the court would, in the future, impose more suspended death sentences. Zhang, quoted in the State-run China Daily, said legislation would be improved to reduce the number of death sentences, and that the SPC would tighten restrictions on the use of capital punishment. He said: “As it is impossible for the country to abolish capital punishment under current realities and social security conditions, it is an important effort to strictly control the application of the penalty by judicial organs.”

In February 2010, China’s highest court has issued new guidelines on the death penalty that instruct lower courts to limit its use to a small number of “extremely serious” cases. The Supreme People’s Court told courts to use a policy of “justice tempered with mercy” that takes into consideration the severity of the crime, the State-run Xinhua news agency quoted court spokesman Sun Jungong as saying in a report on February 9. The guidelines reflect the court’s call in July of 2009 for the death penalty to be used less often and for only the most serious criminal cases.

On March 11, 2010, in his report to the annual session of the National People’s Congress, the chief justice of the Supreme People’s Court, Wang Shengjun, in keeping with the government’s customary secrecy, gave no figures for the number of death sentences or executions. Wang only noted that the courts concluded 767,000 criminal cases and sentenced 997,000 people, down by 0.2 percent and 1.1 percent respectively. But again he did not say how many were related to death sentences, and, for the first time, he did not even announce – nor did official media sources report – how many people were “sentenced to death, life imprisonment, or more than five years in prison,” the formulated phrase used in the past by the country’s Supreme Court to speak of “severe penalties” resulting from trials. “The courts strictly controlled the number of death sentences and prudently used death penalties,” is all Wang’s report says. The courts implemented the policy of “tempering justice with mercy,” it says. The SPC itself dealt with 13,318 cases of various types and concluded 11,749 cases in 2009, up 26.2 percent and 52.1 percent year on year, respectively.

It can be safely presumed that the great majority of these cases (for which they hired literally hundreds of new judges) are death penalty review cases, as the SPC doesn’t have jurisdiction over many other cases. One Chinese scholar estimates that death penalty review in and after 2007 would be more than 90% of the SPC’s case load. “Death penalty cases will make up more than 90 percent of the total number of cases heard by the court,” said Ni Jian in an opinion piece appeared on November 21, 2007, in The Beijing News.

Under such circumstances and considering that the SPC dealt with 13,318 cases of various types and concluded 11,749 cases, an approximate but realistic estimate would put the number of death sentences in 2009 at around 10,000.

At the same session of the National People’s Congress, China’s Chief Justice Wang Shengjun said that courts will take actions on judicial corruption to prevent abuse of judicial power. The Supreme People’s Court will “strengthen capacity building and act as a model for local courts,” Wang said. The pledge came after Huang Songyou, former SPC vice president, was sentenced on January 19, 2010 to life imprisonment for taking bribes and embezzlement. Wang said nearly 800 court officials were punished for violating laws in 2009.

The reform, which took effect on January 1, 2007, is considered one of the most significant reforms concerning the death penalty in the last twenty years. It signals a turn-around from the “hit hard” approach taken on in the Eighties that brought the Supreme Court to delegate final decisions regarding capital punishment cases to the lower provincial courts.

According to the new provision, the review of each case should be carried out by three judges of the Supreme Court, who must re-examine all evidence, the laws applied, the appropriateness of the sentence, the arguments of the preceding trial and they must hear the accused in person or by letter before reaching a final decision. If the judges find the evidence insufficient, the sentencing inappropriate or the trial arguments illegal, they present the case to the Judicial Committee of the Supreme Court. The committee examines the case along with a prosecutor from the Office of the Attorney General Supreme of the People. The cases which have not yet gone to a public trial of appeal will not be reviewed by the Supreme Court, but are sent back to a lower court for public trial.

In fact, as of July 1, 2006, all appeal processes concerning capital cases should have received public hearings in China. Defense attorneys were to have their arguments heard and the accused were to give depositions. These hearings were to be video-taped to allow for their re-examination. To date, provincial High Courts have approved death sentences with only legal precedent as their guide and without hearing from defense attorneys or the accused.

On May 22, 2008, China’s Supreme Court and Ministry of Justice jointly issued regulations on the protection of defense lawyers’ roles in capital cases to ensure that defendants’ legal rights were upheld. The regulations build upon existing documents on defense lawyers’ work in capital cases. They also standardize the lawyers’ duties, the official said. Some provisions of the regulations include: legal aid institutions must designate lawyers with criminal defense experience in capital cases; lawyers shall not transfer such cases to assistants and must meet the defendant before trial; judges must “earnestly listen” to lawyers’ suggestions, ensure that lawyers are able to complete their presentations, and explain why defense lawyers’ motions are honored or denied; the Court must inform “interested parties,” lawyers and prosecutors of any date change for court hearings three days ahead of time; the Court must notify lawyers if prosecutors submit new evidence or re-evaluate the case before a re-trial.

After the reform, there were also cases of pardon and cases of compensation for wrongful detainment, such as that of the two wrongly condemned death row inmates who were granted State compensation after they were found not guilty of heroin trafficking on appeal and set free in July. On November 15, 2009, Mo Weiqi was paid 50,507.49 yuan (US$7,398.20) while Xie Kaiqi received 48,491.67 yuan, China Youth Daily reported. Mo was sentenced to death by the intermediate court of Dehong Dai and the Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture on September 17, 2008. Mo appealed to the Yunnan Higher People’s Court eight days after his conviction, insisting that he had no idea about the heroin in his luggage. Trafficker Xiong Zhengjiang was later seized and confessed to police that Mo and Xie had no idea about the narcotics hidden in their luggage. The compensation was calculated based on last year’s average daily income for domestic workers and the number of days Mo and Xie were in prison. Mo had been jailed for 451 days and Xie had spent 433 days in a detention center.

On May 30, 2010, two new regulations were jointly issued by the top court, the top prosecutor, the ministries of public security, State security and justice, regarding specific rules on collection of evidence and review in criminal cases. Evidence obtained illegally – such as through torture during interrogation – cannot be used in testimony, particularly in cases involving the death penalty, according to the two regulations. The first regulation sets out principles and rules for scrutinizing and gauging evidence in cases involving the death penalty, and the other sets out detailed procedure for examining evidence and for excluding evidence obtained illegally. They are expected to cut down on death sentences and reduce forced confessions, experts say. The regulations make it clear that evidence with unclear origin, confessions obtained through torture, or testimony obtained through violence and intimidation are invalid, particularly in death sentences. The new regulations define illegal evidence and include specific procedures on how to exclude such evidence. Lu Guanglun, a senior judge at the Supreme People’s Court, said such details do not exist in the Criminal Procedure Law and its judicial interpretations. “This is the first time that a systematic and clear regulation tells law enforcers that evidence obtained through illegal means is not only illegal but also useless,” said Zhao Bingzhi, Dean of the law school at Beijing Normal University. “Previously we could only infer from abstract laws that illegal evidence is not allowed. But in reality, in many cases, such evidence was considered valid,” he said. “This is big progress, both for the legal system and for better protection of human rights,” he said. “It will help reduce the number of executions.”

According to the Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) of the PRC, after receiving an order from the Supreme People’s Court to execute a death sentence, the People’s Court at a lower level shall cause the sentence to be executed within seven days. A death sentence may be executed on the execution ground or in a designated place of custody. The judicial officer directing the execution shall verify the identity of the criminal, ask them if they have any last words or letters and then deliver them to the executioner for execution of the death sentence. Executions of death sentences shall be announced but shall not be held in public. After a death sentence is executed, the court clerk on the scene shall prepare a written record of it. The People’s Court that caused the death sentence to be executed shall submit a report on the execution to the Supreme People’s Court. After a death sentence is executed, the People’s Court that caused the death sentence to be executed shall notify the family members of the executed.

Despite these first signs of an at least superficial approach to guaranteeing civil liberties, both violent and non-violent criminals continue to be cast indiscriminately into the meat-grinder of Chinese justice. They are prosecuted and dispatched with a lack of transparency, according to Chinese lawyers who complain of blocked access to their clients and say many confessions are still coerced.

There are also double standards: public officials accused of embezzling billions of yuan receive suspended death sentences that spare their lives, while ordinary citizens convicted of stealing far less die by lethal injection or a single gunshot to the head, according to lawyers and court records.

On August 5, 2009, a businesswoman in Zhejiang Province was executed for fraud. Du Yimin was convicted of “fraudulent raising of public funds” and sentenced to death in March 2008. Her appeal was rejected on January 13, 2009. According to the verdict, she had illegally raised approximately 700 million yuan (US$102 million) from hundreds of people investing in her beauty parlors. Her lawyer stated that Du Yimin should have been convicted for the lesser offence of “illegally collecting public deposits,” which carries a maximum sentence of 10 years’ imprisonment and a fine of 500,000 yuan (US$73,000). Du Yimin’s death sentence caused a debate about the consistency in the application of the death penalty in the People’s Republic of China. The day before she was sentenced to death, an official who used 15.8 billion yuan of public funds to cover his personal spending was sentenced to a fixed term of imprisonment.

The peak times for executions are around the holidays. Generally, the Chinese government “celebrates” national holidays executing massive numbers of condemned and, traditionally, a wave of executions has preceded the “celebration” of the Chinese National Day and the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, as well as the opening of sessions of the National People’s Congress.

The Chinese Government has used the “war on terrorism” as a pretext to harden its’ iron fist against all forms of political or religious dissent in the country. In particular, China passes off repression against Tibetans and the Uyghurs as part of the war on terrorism and exercises pressure on its neighbors such as Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Nepal and Pakistan to force them to repatriate exiled members of Xinjiang’s Muslim Turkic-speaking Uyghur population. Many of the repatriated Uyghurs have suffered serious violations of their human rights including torture, unfair trials and, also, execution.

Arrests and prosecutions for “endangering State security” (ESS) in 2009 retreated from the “historic levels” reached in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics in 2008 but remained high, according to new estimates produced by The Dui Hua Foundation. During 2009 as many as 1,150 individuals were arrested and nearly 1,050 individuals indicted on State security charges in China. The foundation said that the acceleration of arrests in the past two years reflected China’s desire to keep control over its restive ethnic regions of Tibet and Xinjiang, where mass riots have occurred, and to impose heavy penalties for “subversive” speech.

According to State press reports 26 people have so far received capital punishment and at least nine have already been put to death for their part in the Xinjiang uprising in July 2009. Most of the names of those sentenced to death or executed appeared to be Uyghur.

In China, death sentences are carried out by such means as shooting or lethal injection. China has recently introduced mobile execution units, which consist of specially-modified vans manned by execution teams and equipped with facilities to put people to death with lethal injections close to trial venues. It is easy to imagine that the transition from firing squads to injections in death vans facilitates an illegal trade in prisoners’ organs. China’s refusal to give outsiders access to the bodies of executed prisoners has added to suspicions about what happens afterward: corpses are typically driven to a crematorium and burned before relatives or independent witnesses can view them.

On August 26, 2009, State media reported two-thirds of organ donors in China are executed prisoners.

In February 2009, the National People’s Congress (NPC), the country’s top legislature, ratified a treaty on extradition with Mexico. Where the death penalty was concerned, the two sides agreed to settle solutions based on individual cases, instead of writing this into the pact as a motive for refusal.

Iran: Still at Second Place on the Podium of Inhumanity

In 2009, once again, Iran has come in second in the bid for the highest number of executions and, along with China and Iraq, finds itself atop the loathsome awards podium of the champion Executioner-States of the world.

On the basis of Iranian newspaper reports and reports from humanitarian organizations such as Iran Human Rights, there were an estimated 402 executions in Iran in 2009, 339 were reported by the official Iranian media. This number is the highest since 2000. In 2008, at least 350 people were put to death (282 of them reported by the official Iranian media).

According to the Iranian Human Rights News Agency (HRANA), the Islamic Republic’s judicial system issued and enforced over 562 execution orders for murder, rape, drugs and prisoners of conscience throughout the Iranian year which goes from March 21, 2009 to March 20, 2010.

On the basis of official Iranian media reports in 2010, as of June 30, there have already been at least 132 executions.

The numbers could be higher as the Iranian authorities do not provide official statistics. The cases that are counted arrive from scattered reports by Iranian journalists or independent sources, that evidently don’t report all executions throughout the nation.

On May 11, 2009, lawyer Mohammad Mostafaei, who is acting for many of the country’s death row prisoners and, in particular, campaigning to save 25 prisoners sentenced to death for crimes committed as minors, said he believes the true number of executions far exceeds estimates given by international human rights groups. “I have calculated there were at least 400 executions in 2008, but it could be 500 to 600,” he said.

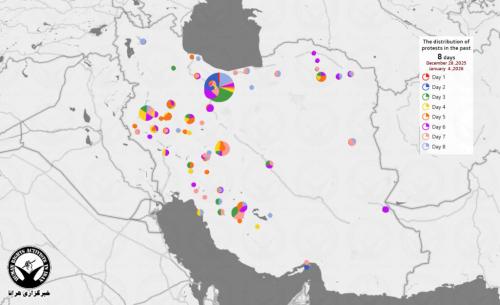

According to the Norway-based NGO Iran Human Rights, the highest number of the executions were carried out in the month before the June 2009 presidential elections (May; 50 executions) and the month after the elections (July; 94 executions, 50 of them in Tehran). Tehran (77), Ahvaz (41), Zahedan (41), Isfahan (40), Shiraz (30), Kermanshah (19) and Kerman (17) were the cities with the highest number of executions.

Most of those executed were either identified only by their initials or not identified at all. Age and time of committing the offence was not provided for many of those executed.

Most of those executed were convicted of drug trafficking (140), murder (56), rape (24), and moharebeh (31). Moharebeh (waging war against God) is a term commonly used by the Iranian regime for those who are involved in armed struggle against the authorities. Twenty-seven of the 31 individuals executed for moharebeh, were convicted of being members of the Baluchi group Jondollah. However, many of these individuals either didn’t have any connection with Jondollah or only carried out web-based activities.

Among the charges used for the death sentences, we also find adultery (2), acts against chastity (1) and unspecific charges such as “disruption of order”. One man who was convicted of adultery sentenced to death by stoning, was hanged in the prison of Sari.

Many of those executed were tried in closed “Revolutionary Courts”.

There were at least 5 minor offenders and 13 women among the 339 executions reported by the official Iranian media.

The Iranian system and its treatment of information regarding the death penalty became even more opaque when, on September 14, 2008, the Mullahs’ Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) warned newspaper editors to censor unofficial reports about escalating numbers of executions, in particular those of minors in the country.

The execution of child offenders continued into 2009, when at least 5 were hanged in Iran, in open violation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child to which it is a co-signatory.

In 2008, at least 13 people under the age of 18 at the time of their crime were executed in Iran, the only country on record to have done so in 2008, while at least 8 minors were put to death in 2007.

Following pressure from the international community, the regime of Mullahs announced a partial and, in practice, ineffectual revision of a practice that places Iran, in a way that seems not be isolated to this situation and in total isolation, at the fringe of the international community. On October 18, 2008, Hossein Zabhi, Deputy State Public Prosecutor, announced that a new Iranian judicial directive, initially issued more than a year before, would ban the execution of juvenile offenders for drug crimes but would keep capital punishment for those convicted of murder. The new directive doesn’t apply to the 120 minors currently on death row, according to Zabhi.

Hanging is the preferred method with which to apply Sharia law in Iran, but stoning was used in at least two cases in 2008 and one in 2009, while shooting was used in at least one case.

Hanging, as practiced in Iran, is often carried out by crane or low platforms to draw out the pain of death. The noose is made from heavy rope or steel wire and is placed around the neck in such a fashion as to crush the larynx causing extreme pain and prolonging the death of the condemned. Hanging is often carried out in public and combined with supplementary punishments such as flogging and the amputation of limbs before the actual execution.

In November 2006, then-Iranian Minister of Justice, Jamal Karimi-Rad, claimed that stoning was not used in Iran, but the facts of following years made the truth abundantly clear.

A man was stoned to death on July 5, 2007, after being convicted of adultery. On December 25, 2008, another two men were stoned, while a third prisoner managed to get out of the hole in which he was buried, avoiding death. The three men were convicted of adultery. The last execution by stoning was reported on March 5, 2009, when a 30-year-old man was stoned to death in the Lakan prison in the northern city of Rasht. These last executions bring the total number of people executed by stoning for adultery to 6 since a moratorium on the practice was requested by then head of the magistrate of Iran, Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi-Shahroudi.

On December 20, 2009, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution first adopted in November by the UN Third Committee that calls on the Iranian Government to abolish any executions carried out without due process of law. Furthermore, it calls for the end of the execution of minors, as well as the use of stoning as a means of execution.

As further testimony to the fervor and fury of the Iranian Regime, mass executions continued in 2009. Between January 20 and 21, nineteen people were hanged in only two days. In the month of May, 52 people were hanged, 21 of whom between May 2 and May 8. The number of executions has increased dramatically since the pro-democracy demonstrations started in the summer of 2009 in Iran. In the month of July, Iran hanged at least 95 people, the highest monthly number of executions in many years. Most of those executed were not identified by name and we can’t know whether the charges mentioned in the reports published by the authorities were true. On July 4, twenty “drug traffickers” were hanged in the prison of Karaj. Another 24 people were hanged on July 30 in the same prison in Karaj for “drug trafficking”.

In 2010, there was no sign of progress. Mass executions continued. In the month of April, at least 28 people were hanged. Between May 8 and 9, eleven people were hanged in two different Iranian cities. Between May 18 and 31, twenty-six people were hanged in seven Iranian cities. The number of the executions increased in view of the first anniversary of the post-electoral uprisings on June 12. Between June 3 and 9, 2010, twenty-two people were hanged in five different cities.

On January 30, 2008, Iran announced that the powerful head of its judiciary must, in the future, approve any executions to be carried out in public and banned all pictures of the events. The new decree was issued by then judicial chief Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi. “Public executions will be carried out only with his approval and based on social necessities,” judiciary spokesman Ali Reza Jamshidi said in a statement. After Shahroudi’s decree public executions decreased. In 2008, at least 30 public executions were held, of which 16 took place after the decree. In 2007, there were at least 110 public executions.

Public executions have continued in 2009: at least 12 people were hanged in public places. In 2010, as of June 30, at least 16 public executions were held.

In 2009, Iran continued to apply the death penalty to clearly non-violent crimes. On October 5, 2009, Rahim Mohammadi was hanged in the prison of Tabriz (northeast of Iran) for “anal rape” and adultery, human rights lawyer Mohammad Mostafaei reported.

In 2009, repression of members of minority religious groups and religious and spiritual movements not recognized by authorities continued in Iran. On July 12, 2009, an Iranian follower of the Ahl-e Haq religious faith (a Shiite offshoot adhering to Imam Ali the first Shiite Imam) was executed in the city of Orumiyeh, for being mohareb, or an enemy of God.

The prohibitionist ideology regarding drugs, prevalent worldwide, once again made its contribution to the death penalty in Iran. In the name of the war on drugs, according to Iran Human Rights, there were at least 140 executions in 2009 compared to 87 carried out in 2008, while according to the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs there were actually 172, almost double the 96 carried out in 2008. Authorities admit that many of the executions in Iran are for drug-related crimes, but human rights observers believe that many of those executed for common crimes such as drugs are actually political dissidents.

The use of the death penalty for purely political motives continued in Iran in 2009. But it is probable that many of the people put to death in Iran for ordinary crimes or for “terrorism,” may well be in fact political opponents, in particular members of Iran’s ethnic minorities, including Iranian Azerbaijanis, Kurds, Baluchis, and Arabs. Accused of being mohareb – enemies of Allah – those arrested are often subject to rapid and severe trials that often end with a sentence of death.

During 2009 the first sentences of death were issued for participation in demonstrations against the fraudulent Presidential Election results of June 12 which saw the re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The first of these executions were carried out in 2010.

However, the death penalty is not the only punishment dictated by the Iranian implementation of Sharia or Islamic law. There is also torture, amputation, flogging and other cruel, inhuman and degrading punishments. These are not isolated incidents and they occur in flagrant violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights that Iran signed and which expressly prohibits such practices.

Every year, thousands of youths are whipped in Iran for consuming alcohol or attending parties with the opposite sex or for outrages against public decency. The Iranian authorities consider whipping an appropriate punishment to combat immorality and such punishments are publicly inflicted as a “lesson to those who watch.”

But the regime particularly outdoes itself in its violation of women’s rights. The segregation of men and women has increased since the first election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who as mayor of the capital first inaugurated the segregation of men and women in the city’s elevators.

In June 2010, Iranian authorities began police patrols in the capital to arrest women wearing clothes deemed improper. Hard-liners say that improper veiling is a “security issue” and that “loose morality” threatens the core of the Islamic republic. Iran’s interior minister has promised a “chastity plan” to promote the proper covering “from kindergarten to families,” though the details are unclear. Tehran police have been arresting women for wearing short coats or improper veils and even for being too suntanned. Witnesses report fines up to $800 for dress considered immodest.

On March 3, 2010, the amputation sentence of one person was carried out in the Karoun prison of Ahvaz. The person was identified as Shoghi Z. (age not mentioned) and was convicted of armed robbery and moharebeh. Another person was flogged in public in Laleh Square of Sosangerd (in the province of Khuzestan). The person was identified as Mehdi H. and was convicted of disorderly conduct.

Iraq

In 2009, for the first time since the fall of Saddam Hussein on April 9, 2003, and the subsequent reinstatement of the death penalty, Iraq has become one of the top Executioner-States in the world, third after China and Iran.

There were at least 77 executions according to information provided by the Iraqi Supreme Court.

“Seventy-seven death sentences were enforced in 2009,” the head of the court Medhat al-Mahmud said in a statement on January 5, 2010. According to the court, the prisoners were found guilty in “cases related to terrorism” and their punishment was applied as a matter of priority.

According to Amnesty International however, at least 120 prisoners were executed by Iraq in 2009, while 366 death sentences were handed down.

There were at least 34 executions in 2008. In 2007, at least 33 executions were carried out.

After the fall of Saddam’s regime, the death penalty was suspended by the Provisional Authority of the Coalition. It was reintroduced after the transfer of power to Iraqi authorities on June 28, 2004. On August 8, 2004, a little more than a month after it came to power, the Iraqi interim government, led by Iyad Allawi, approved a law that reintroduced the death penalty for homicide, kidnapping, rape and drug-trafficking.

On May 30, 2010, the Iraqi Council of Ministers extended the application of the death penalty for economic crimes to the stealing of electricity. The practice of taking a line from the national network of electricity is common practice in deprived rural and urban areas in Iraq.

With the execution of ex-Rais Saddam Hussein for crimes against humanity on December 30, 2006, there were 65 executions in Iraq during the year. To this were added other exponents of the deposed regime in 2007: Barzan al-Tikriti, Awad Hamed al-Bandar, and Taha Yassin Ramadan.

On March 2, 2009, the Iraqi High Tribunal acquitted former deputy prime minister Tareq Aziz, for involvement in “the Friday prayer incident,” referring to the deaths of dozens of Shiites in 1999 in the Sadr City district of Baghdad and in the central shrine city of Najaf.

On March 11, 2009, two of Saddam Hussein’s half-brothers, former interior minister Watban Ibrahim al-Hassan and director of public security Sabawi Ibrahim, were sentenced to death for crimes against humanity. The trial dealt with the 1992 execution of the 42 merchants accused by Saddam’s government of price gouging while Iraq was under U.N. sanctions. Hussein’s former foreign minister, Tariq Aziz, was convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison for his role in the execution of the 42 merchants. The conviction was the first against Aziz.

On January 25, 2010, Ali Hassan al-Majid, the cousin of former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, was executed for crimes against humanity, a government spokesman said. The week before, Al-Majid – nicknamed “Chemical Ali” by the Western media – was sentenced to death for ordering the gassing of Kurds in the Iraqi village of Halabja. In March 1988, Iraqi jets swooped over the village of Halabja and sprayed it with a deadly mix of mustard gas and the nerve agents Tabun, Sarin and VX. It is believed that about 5,000 people died in the attack, three-quarters of them were women and children. For Chemical Ali this was the fourth sentence of capital punishment. Majid was sentenced to hang in June 2007 for his role in a military campaign against ethnic Kurds, code-named Anfal, that lasted from February to August of 1988. In December 2008, he also received a death sentence for his role in crushing a Shia revolt after the 1991 Gulf War. In March 2009, he was sentenced to death, along with others, for the 1999 killings of Shia Muslims in the Sadr City district of Baghdad.

DEMOCRACY AND THE DEATH PENALTY

Of the 43 retentionists, only 7 countries are considered liberal democracies. This definition, as used here, takes into account the country’s political system and its respect towards human rights, civil and political liberties, free market practices and the rule of law.

There were 3 liberal democracies that carried out executions in 2009, and they accounted for 60 executions between them, about 1% of the world tally. These were: The United States (37), Japan (7) and Botswana (1). In 2008 there were 6 (with Indonesia, Mongolia and Saint Kitts and Nevis) and they carried out a total of 65 executions.

In Indonesia, 2009 was the first year without an execution since 2004, while India has not carried out an execution in five consecutive years.

United States: The Number of Death Sentences and death row Inmates Continues to Decrease

Executions

Executions rose in 2009 compared to the last two years. There were 52 executions; there were 37 executions in 2008 and 42 in 2007.

The data is not consistent however, because during the two preceding years for a number of months (from September 2007 to May of 2008) a de facto moratorium was in place while waiting for a Supreme Court decision on the constitutionality of the protocol for lethal injection (the case of Baze v. Rees in Kentucky, April 16, 2008).

Executions took place in 11 of the 35 States with the death penalty: Texas (24), Alabama (6), Ohio (5), Georgia (3), Oklahoma (3), Virginia (3), Florida (2), South Carolina (2), Tennessee (2), Indiana (1) and Missouri (1).

The number of executions in 2009 was still 47% less than that recorded in 1999 (98).

51 were carried out by lethal injection, 1 with the electric chair (Virginia). All those executed were male: 23 whites, 22 blacks and 7 Latin-Americans.

Relevant Cases

During 2009 the most followed executions were those of John Allen Muhammad and Kenneth Biros.

John Allen Muhammad, known as “The Washington Sniper”, was executed on November 10 in Virginia. He was accused with at least 10 homicides which occurred in the Washington D.C. Area in 2002.

The execution of Kenneth Biros, carried out on December 8 in Ohio, was the first utilizing the new lethal injection protocol. According to the new protocol, the lethal injection is composed of an overdose of barbiturates, specifically of sodium thiopental. Sodium thiopental was already present in the former protocol and was the first of three drugs injected, followed by a muscle-paralyzer and a heart-stopping poison.

Death Sentences

2009, for the 7° consecutive year, saw a decrease in death sentences, arriving at 106, the lowest number since the re-introduction of the death penalty in 1976. There were 111 death sentences in 2008 and 119 in 2007. The 106 death sentences of 2009 represent a 2/3 reduction since the record of 328 death sentences handed down in 1994.

The most notable drop was that of Texas, which had 11 death sentences compared to the average of 34 annually throughout the nineties. A former assistant district prosecutor in Houston, Vic Wisner, attributes the fact to a “constant media drumbeat” about suspect convictions and exonerations which “has really changed the attitude of jurors.” Wisner points out that while opinion polls continue to show the “theoretical” support of the death penalty, when individuals are called to serve on a jury, the possibility that an error of justice could lead to an irreversible execution puts the brakes on the actual use of the death penalty.

Besides that of Texas, the other highly revealing fact comes from out of Virginia, a State which is generally only second to Texas in the number of executions. While throughout the nineties Virginia sentenced an average of 6 people to death a year, only one death sentence was handed down in 2009 and there have been a total of only 6 death sentences in the last five years.

Contrary to national trends is the State of California, where death sentences have increased: there were 29 in 2009, while there were 20 in 2008. Of the condemnations, 13 were handed down in Los Angeles County. In short, the County of Los Angeles alone condemned more people to death than the entire State of Texas.

Death Row

In the first 9 months of 2009, the number of inmates on death row decreased by 34, from 3,297 to 3, 263. The highest number of inmates on death row was reached in the year 2000 at 3,593 inmates. Since then the number has diminished regularly.

As has been the case for many years, the death row of California is the biggest in the United States. As of October 1, 2009 it held 694 inmates. If it’s indeed the case that in 2009 California handed down more death sentences than all the other States, the principal reason for the size of its death row can only be blamed on the State’s procedure for appeals which is longer than in other States with certain courts holding a particularly hard-line on the protection of civil rights, all resulting in a low number of executions (there were 13 in 1976).

After California, the States which have death row populations exceeding 100 are: Florida (395), Texas (339), Pennsylvania (223), Alabama (201), Ohio (170), North Carolina (169), Arizona (132) and Georgia (108).

The lowest death row populations are those of New Hampshire and Wyoming (1) and those of Montana and New Mexico (2), besides that of the State of New York, which is empty.

In the last 10 years, the death row which has grown the most proportionally is that of the Federal justice system: in 2000 it had 19 inmates and by the end of 2009 there were 58 inmates, while 8 men are being held on the death row of the Military justice system.

Along racial lines, 44.4% of inmates are white, 41.6% are black, 11.6% are Latin-American and 2.4% belong to other ethnic groups. Divided by gender, there are 53 women and 3,224 men on the United States’ death rows. Women represent 1.6% of the death row population in the U.S.A. In 2008, there were 58 women.

Legislation

Eleven States considered legislative proposals to repeal the death penalty in 2009, a considerable increase from previous years.

The costs of the death penalty – linked to the lengthy procedures surrounding capital cases and detentions in maximum security prisons – were frequently cited in legislative debates about the death penalty.

Some proposals had limited life-spans in the legislature, while others were more successful.

On March 18, 2009, New Mexico abolished the death penalty, becoming only the second U.S. State to do so in more than forty years, after New Jersey on December 13, 2007. Although New Mexico is a southern State, bordering the “champions” of the death penalty such as Texas and Oklahoma, it has only carried out one execution in the last 49 years.

On April 21, 2009, the House approved a bill to eliminate the death penalty in Colorado and shift funds currently used to prosecute death-penalty cases to deal with the growing backlog of more than 1,400 unsolved homicides. However, the Senate defeated the proposal on June 6 by one vote. It is estimated that 3 out of every 10 homicides in Colorado go unsolved. The law was backed by family members of over 500 victims in unsolved cases. The most recent execution occurred in 1997.

In Montana, the State Senate voted to abolish the death penalty on February 17, 2009, but the House Judiciary Committee voted against the bill on March 30. Montana has executed 3 people since reinstatement of the death penalty in the 1970s. The most recent execution occurred in 2006, but this involved a “volunteer”, a condemned person who renounced available appeals.

In Maryland, for a number of weeks, it seemed possible that an abolitionist law would be passed following a recommendation expressed on December 13, 2008 by the Commission on the Death Penalty put together by Governor Martin O’Malley. Blocked by the Senate, the proposal was transformed into a compromise bill (SB 279) which makes it more difficult to issue a death sentence. The bill restricts capital punishment to murder cases with biological evidence such as DNA, videotaped evidence of a murder or a videotaped confession. The Democratic governor, who is Roman Catholic, opposes capital punishment and backed a bill that would have abolished the death penalty altogether. But he says the bill that passed is a step toward justice. Maryland has executed five people since reinstating the death penalty in 1978. The most recent execution occurred in 2005.

In Kansas, Republican Senator Carolyn McGinn presented an abolitionist bill that was approved by the Senate Judiciary Committee, which, however, on March 4, 2009, decided to send the bill to an interim study committee rather than advancing it to the chamber floor for debate. On January 29, 2010, the Senate Judiciary Committee again passed the bill that would abolish the death penalty, but on February 19 the Senate voted 20-20, one vote less than the 21-vote majority needed for the passage of the bill. No one has been executed in Kansas since the death penalty was reinstated in 1994.

On June 5, 2009, the Governor of Connecticut, M. Jodi Rell, vetoed the bill, approved on March 31 by the State House and on May 22 by the State Senate, which would have abolished the death penalty replacing it with life imprisonment without parole. The last execution in Connecticut was that of Michael Ross on May 13, 2005, but this was also the case of a “volunteer” who insisted on being executed. The last execution before this was in 1939.

In New Hampshire, the State House voted to repeal capital punishment on March 25, 2009, but the Senate voted to put off action on the bill on April 29, as the democratic governor, John Lynch, had promised to veto it. As a compromise the Senate and the House approved a bill that instituted a “Study Commission” on the death penalty. The State’s last execution was in 1939 and currently there is only one person on death row.

Laws intended not to limit but to expand the use of the death penalty were approved in Virginia, where Governor Timothy M. Kaine exercised his veto power on March 27, 2009. Three different laws would have expanded the death penalty to criminals who assist in murders (the so-called “triggerman rule”) or who kill fire marshals or auxiliary police officers. It was the third year in a row Kaine vetoed the “triggerman” bill.

In Utah, a proposal that would have amended the State constitution to speed up the appeals process, particularly in death-penalty cases, failed in the House on March 12, 2009.

In New Hampshire, on March 10, 2010, the Senate voted against a bill to apply the death penalty in home invasion murder cases.

On March 18, 2010, in Maryland, the House Judiciary Committee rejected a bill that would have imposed the death penalty for the murder along with the sexual assault of a child.

However, moratoriums established in recent years still hold, such as the de jure moratorium in Illinois and those de facto moratoriums in the States of Kansas, New York, North Carolina, South Dakota and in the Military Administration and those created by appeals against execution protocols in California, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska and the Federal justice system.

Methods of Execution

On May 28, 2009, Nebraska adopted lethal injection as its principal method of execution, as it was previously the only State to have the electric chair in use as its principal means of execution.

After the choice of Nebraska, today all the States use lethal injection as their primary method of execution. In some States the “old methods” are still available upon request by the condemned and generally only for crimes committed before the adoption of lethal injection.

The electric chair is still available in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. The gas chamber is still available in Arizona, California, Maryland, Missouri and Wyoming. The firing squad is available in Oklahoma and Utah. Hanging is available in New Hampshire e Washington.

On November 17, 2009, in Virginia, Larry Bill Elliott was put to death upon his request by electric chair.

On June 17, 2010, Ronnie Lee Gardner was executed by a firing squad at Utah State Prison in Draper. Gardner, 49, white, was the first death row inmate to be executed since 1999, and the first by firing squad in the United States since 1996. He was strapped to a black metal chair surrounded by sandbags to stop ricocheting bullets. A target was then pinned over his heart, a hood placed over his head, and five volunteer marksmen armed with 30-caliber rifles opened fire from behind a wall. Only four of the weapons were loaded with live rounds and one contained a wax bullet, allowing the marksmen to retain some doubt over whether they fired the fatal shot. Gardner was condemned to death in 1985 for double homicide.

With that of Gardner, there have been 1,216 executions in the U.S.A. From 1976 to the present: 1,042 by lethal injection, 157 with the electric chair, 11 in the gas chamber, 3 by hanging, 3 by firing squad.

In November of 2009, Ohio was the first State to switch its lethal injection method from the three-drug cocktail used in almost all States to a one-drug protocol. The protocol was modified after the botched execution of Romell Broom in September, with medical professionals making at least 18 attempts to find a suitable vein in his arms and lower legs. The single-drug technique amounts to an overdose of the anesthesia, sodium thiopental. In cases where a suitable vein cannot be located, a combination of 2 chemicals will be injected into muscle. Those drugs will be midazolam and hydromorphone.

On March 2, 2010, Washington became the second State to change to the single-drug protocol, but the three-drug protocol remains an option for inmates who request it. Several other States have taken steps towards modifying their protocol.

The Supreme Court

In recent years the Supreme Court has made “milestone” decisions prohibiting the execution of minors, the mentally ill and confirming the constitutionality of lethal injection. The sentences of 2009 regarded much less generalized themes, although some would seem to suggest themselves as “interlocutors” to the controversies that will surround the death penalty in the years to come.

On March 9, 2009, with the sentence in Thompson v. McNeil, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Florida death row inmate William Thompson who claimed that his 32-year imprisonment constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment. It’s an argument which has often been presented by death row inmates and has always been rejected. This time, however, two Justices – John Paul Stevens and Stephen Breyer – voted in dissent. Justice Stevens called the treatment of the defendant during his 32 years on death row “dehumanizing,” noting that a punishment of death after significant delay is “so totally without penological justification that it results in the gratuitous infliction of suffering.”

Sooner or later, the Supreme Court will find itself discussing an even more clamorous case, that of Romell Broom who, as already mentioned, should have been executed in Ohio on September 15, 2009. After strapping the condemned to a gurney and having tried for two hours to inject needles into veins that were either too difficult to find or too fragile, the execution was suspended. The failure convinced the State of Ohio to modify its execution protocol, but the defense called for an appeal to the Supreme Court sustaining that after the anxiety and stress of the failed execution, a new attempt would constitute “cruel and unusual punishment”.

On August 17, 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court, in an exceptional move, ordered a U.S. district court in Georgia to hear new testimony in the case of Troy Davis. For the first time in 50 years, the Court has accepted a direct appeal presented to the Court not having come from an inferior court. In fact, in Georgia there is a special anti-terrorism law that limits the rights of appeal for those condemned of, among other things, the murder of a police officer, and Davis is accused of having killed a police officer in 1989. The appeals of Davis were all declared “null” for their delayed presentation as stipulated by the anti-terrorism law, without considering new evidence that would have exonerated the condemned including written declarations from almost all the witnesses that testified against him, revealing that they were pressured by police (Davis, a black man, is accused of killing a white police officer twenty years ago). “The substantial risk of putting an innocent man to death clearly provides an adequate justification for holding an evidentiary hearing,” said Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the court. Justice Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas dissented, calling the court’s action “extraordinary ... one not taken in nearly 50 years.”

On November 30, 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a sign of the times for a nation at war on two fronts, unanimously overturned the death sentence of a Florida veteran whose “combat service unfortunately left him a traumatized, changed man,” as the Court put it in Porter v. McCollum, involving Korean war veteran George Porter. This decision appears to be the first in which the court cited “post-traumatic stress disorder” from military combat as the kind of crucial evidence that calls for leniency. He was charged with the October 1986 shooting and killing of his ex-girlfriend Evelyn Williams and her new boyfriend Walter Burrows. There was little doubt of his guilt. But his jury was never told, and his appointed lawyer did not know, of his valiant military service more than 3 decades earlier.

Exonerations and Commutations

“Exonerated” is a technical term that, in the U.S. justice system, indicates an individual convicted in the first degree but absolved on appeal. As is well noted, appeals in the United States are not one-time, unrepeatable events, but can be presented every time the defense feels that it has discovered new elements relevant to exonerating the condemned. It is not rare that certain “appeals” can be presented 20 years or more after initial sentencing. In some cases, the “exonerated” are obviously innocent (in cases where DNA evidence proves the guilt of someone else, for instance), in other cases, there is dismissal on appeal for “lack of evidence” or because, after so many years from the actual crime, the Public Prosecutor no longer has credible witnesses to testify.

In 2009, nine men on death row were released from prison, bringing the total number of “exonerated” to 139 from 1973 to December 31, 2009.

Three were absolved: Daniel Wade Moore (white) in Alabama; Herman Lindsey (black) in Florida; Nathson Fields (black) in Illinois. The other 6 had charges against them dropped by Public Prosecutors: Ronald Kitchen (black) in Illinois; Yancy Douglas (black) in Oklahoma; Paris Powell (black) in Oklahoma; Paul House (white) in Tennessee; Michael Toney (white) in Texas; Robert Springsteen (white) in Texas.

Besides complete exonerations, 3 condemned received commutations to life imprisonment thanks to political interventions.

On February 12, 2009, in Ohio, Governor Ted Strickland commuted Jeffrey D. Hill’s death sentence to a term of 25 years to life.

On May 19, 2010, in Oklahoma, Governor Brad Henry granted “clemency” to Richard Tandy Smith and commuted his death sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

On June 4, 2010, in Ohio, Governor Ted Strickland commuted Richard Nields’ death sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

On July 22, 2009, the Innocence Project released a new report pointing to problems with eyewitness identifications in criminal cases. The report, “Reevaluating Lineups: Why Witnesses Make Mistakes and How to Reduce the Chance of a Misidentification,” states that over 175 people (including some who were sentenced to death) have been wrongfully convicted based, in part, on eyewitness misidentification and later proven innocent through DNA testing. But DNA testing is not a solution to the problem since it is only available in 5-10% of all criminal cases, according to the report. The findings in the report specified that in 38% of the misidentification cases, multiple eyewitnesses misidentified the same innocent person; fifty-three percent of the misidentification cases, where race is known, involved cross-racial misidentifications; in 50% of the misidentification cases, eyewitness testimony was the central evidence used against the defendant (without other corroborating evidence like confessions, forensic science or informant testimony).

The Cost of the Death Penalty

Besides questions of judicial error, which have been debated heatedly in recent years, is the question of “cost.” As is well known, in contrast to the European systems of justice, in the United States the various courts have very precise budgets which must be accounted for to the last cent. If prosecutors wish to try cases involving the death sentence they must provide more evidence, more lab results, more testimony and the State must provide the accused with better legal counsel. This all has its costs, which increase in successive phases of the legal process, because those who risk death have a right to increased free legal assistance, lab analysis to contrast that of the Prosecution (at cost to the State), and to hire expert witnesses (also at cost to the State) and to present a series of appeals and recourses that are not available to those who risk imprisonment. This means that when prosecutors begin death penalty cases, they start a process which drains funds from the State, and that, often, because of these expenses, there are less funds for other activities.

In many interviews with politicians and in bills presented in numerous States, the problems related to the “cost of the death penalty” came under focus with consideration of an alternative: giving up on capital punishment, which usually involves people for which there is already ample proof for conviction and using the money saved to solve cases where criminals have yet to be identified.

Studies have calculated that approximately 50% of the death sentences handed down eventually are transformed into sentences of life imprisonment after the appeals process. These percentages do not include exonerations, and therefore cannot be attributed to errors of justice, but instead indicate a waste of public funds by the judicial process. The suspicion is that district attorneys, who often aim for political careers, seek to try death penalty cases for personal prestige, regardless of the costs. Other studies have shown, even in cases where the death sentence “holds,” keeping a person in prison for life costs ten times less than keeping someone on death row for a few years and then putting them to death. Of course, there is always the media to show that the family of the victim after an execution is “very satisfied and finally relieved,” but to this, which always helps politicians garner consensus, some associations of victims’ families are answering by saying that, in the interest of the victims, it would be better to direct funds to “cold cases,” those thousands of unsolved cases that present themselves every year. The satisfaction of some dozens of victims’ families who get to see “their perpetrator” put to death comes at the cost of thousands of families who won’t see “their perpetrator” brought to justice because there are no funds to look for them. This “quantitative” reasoning, as could be expected from American culture, is having success, and many politicians traditionally in favor of the death penalty are starting to change their minds. The question of “cost” is bound to become more compelling in the years to come and, together with the question of errors of justice, should bring about important changes.

Doing away with capital punishment can potentially save States in the U.S. hundreds of millions of dollars annually, according to a new study released by the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) on October 20, 2009.

Richard Dieter, author of the study and DPIC’s director, assesses the data in the following way: “It is doubtful in today’s economic climate that any legislature would introduce the death penalty if faced with the reality that each execution would cost taxpayers 25 million dollars, or that the State might spend more than 100 million dollars over several years and produce few or no executions. Further down the road, only 1 in 10 of the death sentences handed down may result in an execution. Hence, the cost to the State to reach that one execution is 30 million dollars.” The number of death sentences handed down in the United States has dropped from roughly 300 a year in the 1990s to 115 a year more recently. Executions are falling off at the same rate, the report says. In the meantime, some 3,300 inmates remain on death row. “The death penalty is turning into a very expensive form of life without parole,” said Richard Dieter.

A 2008 study in California found that the State was spending $137 million a year on capital cases. A comparable system that instead sentenced the same offenders to life without parole would cost $11.5 million, says the DPIC report, citing the study’s estimates. New York spent $170 million over nine years on capital cases before repealing the death penalty. No executions were carried out there. New Jersey spent $253 million over 25 years with no executions. That State also repealed capital punishment. Some officials may be tempted to try to cut capital-punishment costs, notes the DPIC report, but many of those costs reflect Supreme Court-mandated protections at the trial and appeals-court levels. In Maryland, a comprehensive cost study by the Urban Institute estimated the extra costs to taxpayers for death penalty cases prosecuted between 1978 and 1999 to be $186 million. Based on the 5 executions carried out in the State, this translates to a cost of $37 million per execution. In the cost study conducted by Duke University, the death penalty costs North Carolina $2.16 million per execution over the costs of a non-death penalty system imposing a maximum sentence of imprisonment for life. Between 1973 and 1999, only 3 of the 89 death-penalty trials in Nebraska resulted in an execution. Those death-penalty cases cost a total of $45 million, according to a State legislative study. In Tennessee, death penalty trials cost an average of 48% more than the average cost of trials in which prosecutors seek life imprisonment, according to a new report released by the Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury. In its review of death penalty expenses, the State of Kansas concluded that capital cases are 70% more expensive than comparable non-death penalty cases. The study counted death penalty case costs through to execution and found that the median death penalty case costs $1.26 million. Non-death penalty cases were counted through to the end of incarceration and were found to have a median cost of $740,000. Florida is spending approximately $51 million per year on the death penalty, amounting to a cost of $24 million for each execution it carries out.

The police has also taken a surprising stance. In April 2010, in California, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) pointed out that in a State that is spending $137 million per year on the death penalty, many homicide investigations have been put on hold due to a budget crisis in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is forcing officers to suspend work on their cases and take days or weeks off because of new overtime limits. In March, the number of hours that officers had to take off was equivalent to removing 290 officers from the police force, reported the Los Angeles Times on April 12, 2010. California has the largest death row in the country and needs a new facility that may cost another $400 million, on top of the yearly costs of capital punishment. Los Angeles County had the most death sentences in the country in 2009.

Yet the most surprising position comes from families of victims. As already discussed, in Colorado an abolitionist law failed to pass by only one vote. It had the full support of Families of Homicide Victims and Missing Persons (FOHVAMP), an association that represents the families of over 500 homicide victims whose cases have yet to be solved. FOHVAMP believes the death penalty is a waste of taxpayers’ money, and it is no deterrent to those who contemplate murder. “We propose to eliminate the death penalty and use those funds to investigate our unsolved murders,” FOHVAMP’s director Howard Morton said. The last execution in Colorado was in 1997, and was the only execution in more than four decades. From the point of view of the victim, explains Morton, catching more killers would be a more effective deterrent than capital punishment and a better use of State funds, because the small satisfaction gained by some people as a result of sporadic executions that are actually carried out pales in regard to the absolute uncertainty and, often, fear, that accompanies the families of the over 1,300 victims whose cases remain to be solved.

The Relation between Crime and Punishment

A survey conducted of the principle exponents of the most important criminological associations in the United States (Radelet & Lacock, 2009), shows that 88% believe that executions are not a deterrent to homicides, 5% believe that they are a deterrent and 7% are undecided.

According to results of a recent poll of 500 police chiefs nationwide, 57 % of the chiefs polled said they agreed with the statement that the death penalty does little to prevent violent crimes because perpetrators rarely consider the consequences when engaged in violence. They suggest more efficient use of resources – such as boosting funding for drug and alcohol abuse programs.

The Uniform Crime Report for 2008, released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in September 2009, showed a decline in the national murder rate. The rate dropped 4.7% in 2008 compared to 2007. Despite a regional decline, the South still has the highest murder rate among the four geographic regions: 6.6 murders per 100,000 people, higher than the national rate of 5.4. The Northeast still maintains the lowest murder rate at 4.2. There were 16,272 murders or non-negligent man-slaughters in 2008, according to the report. The South has accounted for over 80% of executions since 1976 (971 of 1,176 executions), while the Northeast accounted for less than 1% (4 of 1,176). Of the 20 states with the highest murder rates in the country, all of them had the death penalty in 2008. Blacks and whites were victims of murder in about equal numbers in 2008, with each accounting for about 48% of murder victims. In death penalty cases resulting in executions, however, 78% of the victims in the underlying murder where white.

Studies have shown that defendants are more likely to receive the death penalty if the victim in the underlying murder was white than if the victim was black.

Opinion Polls