12 January 2017 :

Niger rarely makes the news. It did a decade ago, when the Italian secret services believed – wrongly – that Saddam Hussein wanted to buy uranium in that country to arm his weapons of mass destruction. More recently it has been mentioned for the incursions of Nigeria’s Boko Haram, or for the risk of terrorist infiltrations from Libya or Algeria. Never is it mentioned that Niger, with a predominantly Muslim population, and with all the problems of a poor and almost forgotten country, has democratic institutions and a political debate essentially secular, capable of enabling a minimum of human development to the nearly 18 million people despite domestic and foreign threats.

And it was about human development, and therefore of human rights, that a delegation of the Radical Party and Hands Off Cain with, among others, Marco Pannella and Sergio D’Elia, discussed such issues with the leadership of that country. The opportunity was provided by the global campaign that the Radicals have been carrying out for over 20 years in favour of a UN resolution to promote a universal moratorium on the death penalty.

According to Hands Off Cain criteria, Niger is a de facto abolitionist country, that is a country where, although the death penalty is in the Criminal Code, there have been no executions for more than 10 years. The latest executions in Niger date back to 1976 and, pursuant to a governmental decision, the de facto moratorium is to last until the definitive abolition of the death penalty. A decision that Niger owes to a new sui generis Minister of Justice in office since April of 2011.

A jurist who, years ago, experienced the hardships of prison for his political beliefs, Marou Amadou is a human rights activist turned minister, who has not sacrificed his ideas and ideals once nominated Minister of Justice, something that rarely happens in Africa (or elsewhere for that matter). He remains attached to his non-violent approach, the same that kept him going during the months in solitary confinement when he was struggling to affirm Niger’s constitutional legality and respect for human rights. Unlike many of his African colleagues, members of the government in Senegal, Ghana, Liberia or Sierra Leone, Marou Amadou has not abandoned his convictions once having obtained the comforts and conveniences that a senior government job often entails. Since being appointed Minister of Justice, and government spokesman, Amadou has not forgotten his activism in favour of human rights, and has initiated, among other things, a series of reforms to permanently delete the death penalty in his country.

In April 2014, Minister Amadou, indeed, commuted nearly all death sentences to life imprisonment, imposing a maximum of 25 years in prison for those who were sentenced to life. In late October of the same year, he also made his Government ratify the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which relegates the death penalty among the violations of internationally recognised human rights.

With this pedigree, Marou Amadou could not be insensitive to the situation of his country’s prisons. Contrary to many of his African colleagues, Mr. Amadou gave us practically unlimited access to two prisons in his country’s capital Niamey: the worst, right in the city centre, and one of the best, that of Kollo, 30 kilometres from the city.

The prison of Niamey is divided into a male section, a female area and a children’s sector. While 46 women and 27 minors are housed in areas that by law can hold 45 and 60 persons respectively, and that structurally do not present serious shortcomings in architectural or sanitary terms, the 1,114 male prisoners are crammed into unhealthy rooms that should accommodate 350!

The prison administration of Niamey did not allow us to document the visit to the male section with pictures or movies for unspecified reasons of “privacy” and “security” – in fact it would not be a pretty sight – but we were able to ask questions about everything.

The male area develops as a kind of labyrinth, where only a lucky few can sleep in dormitories, with virtually no windows, and a toilet that is separated from the sleeping area by a cloth. The rest of the detainees are massed into open areas where life takes place during the day and where, given the incredible overcrowding, everyone sleeps in temporary bunks that have become permanent for a lack of a forthcoming solution. Outdoor spaces, which are home to nearly 900 people, recall the hustle and bustle of the souks, where there is no separation between the areas where you can walk, if only to go to the dilapidated bathroom or the shower – a dozen poor taps for more than a thousand people – and the areas where people sleep or eat. Dozens of bunks arranged with every kind of material are covered by towels or mats hanging from wires attached to the walls, and serve to defend people from the 40 degree temperatures of the dry summer, or the heavy thunderstorms of the rainy season. Of course, when the number nears 1,500 inmates, authorities do “evacuate” dozens of people, but in recent times, we were told quietly by the guards, the figure never dropped below 1,000 prisoners – almost 700 more than the legal maximum capacity.

Just as in Italy, also in Niger the administration of justice has fallen under very uncertain times. In fact, of the 1,114 people we found in the prison of Niamey at the end of November 2014, only 411 had a final sentence. None of the male inmates were working or going to school; few speak or understand French, the official language of Niger. Even the mosque, usually incredibly immaculate even in the poorest countries, reflects the dire situation of the dramatic overcrowding. International cooperation, which is rarely interested in prisons, is present with a small project supported by the Belgian government that provides schooling for children and some working activities for women. The Americans have offered financial support for the construction of a prison that would accommodate a thousand people according to U.S. standards. Since the co-financing should be predominantly coming from the local government, it is difficult to imagine a date for the start of work. The women’s section of the prison, and that which host minors, only boys, is significantly better that that of the adults: there are no problems of overpopulation, and almost everyone works at knitting, carpentry, sewing and batik colouring. In the department of minors, we met 27 boys, some ready for a working session, while others were in class to learn how to count in French. In talking to the boys, we gathered that, in many cases, the validation of the arrests takes place without any kind of legal assistance. A little boy candidly confessed to being 12 years old – an age at which in Niger one should not be in prison. It is hoped that the report we made to the timid representatives of the United Nations, who by then had joined our visit, will enable an immediate release of the child.

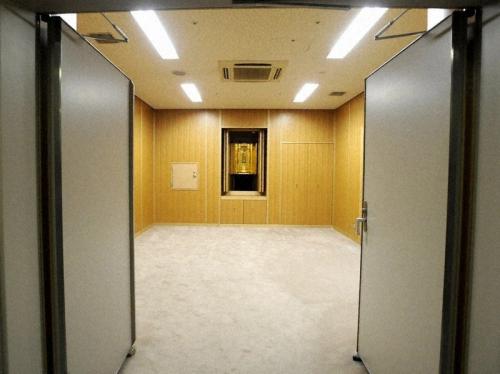

The visit to the prison in Kollo presented a situation radically different from what we found in the capital. The complex, built with the typical mud red earth of central Africa, is organised into four parts: a female section, where there were 24 women in a rather narrow but fairly kept environment, and a male sector divided among “definitives”, those in remand, and State “officials”. Built in 1987 to house 1,500 inmates, at the time of our visit the prison contained 283 people: 161 convicts, including four women and two minors; 124 in remand, including 20 women and one minor. The male detention areas revolve around a central zone where a place for prayers is built, it is usually run by an inmate serving as imam. Unlike the prison of Niamey, here the “mosques” were very well maintained. The rooms host from a minimum of four to a maximum of eight beds that are open from 6.30 am to 7 pm. Here, too, the windows are cracks in the walls. Much of the day is spent outdoors in total indolence, where a paltry single meal a day is served – the rest of an inmate’s energy is guaranteed by food provided by their family. The “officers”, about 30 people indicted or sentenced for crimes against the public administration, are organised as a small community, separate from other prisoners in a much better kept place.

In Niger there is no prison police, and the detention centres are guarded by the military; medical personnel in Niamey were wearing civil suits, in Kollo everybody was in uniform. Just outside the walls of the institute, earlier this year, the administration expanded a vegetable garden, where six inmates grow vegetables that eventually will be used for the meals of detainees.

For more than two hours, we interacted freely with the detainees in all sections of both institutions, at least with those who understood French. But in the section of the condemned, besides the few one on one conversations, something different happened, one might say “magical”. At the invitation of the Director of Protocol of the Ministry of Justice, Marco Pannella addressed the detainees to explain who we were and why we were visiting them.

It is rare that Marco Pannella takes the floor only to introduce himself and obey the rituals of protocol: as a matter of fact, he cleared his throat and launched into a sermon. A sermon in the most noble, the most classical sense of the word. Expressing the joy that filled his heart for his presence there with hundreds of people deprived of their personal freedom, Pannella elaborated on a Latin motto “Spes contra spem” that recently, and with an increasing insistence, he is repeating wherever he can: one must be “hope” against the trivialisation of having hopes, hopes that are not realised because they are hollow proclamations that fail to give substance to the necessity to envisage alternative scenarios to current problems. The audience listened to the translation in the local dialect in a hypnotised silence.

In Africa, elderly people are special persons. Where life expectancy is around age 50 at the most, being in front of an ultra-octogenarian (Pannella was born in 1930) in blue jeans and a long pink scarf – a gift of the female inmates of the Niamey prison – who wants to engage an audience in the scorching midday sun of Niger, in itself commands a respectful attention. And when the wise old man, who came from who knows where and who knows why, wants to give hope to others through the example of his life, with his “being there”, demonstrating a sincere and proactive interest in the events of their past, then the atmosphere takes a chemical twist that can transform a few minutes of words in a memorable event. The proof of the effectiveness of Pannella’s words was the force with which the Director of the Penitentiary Administration of Niger translated his words into one of the local languages. A translation that sparked a long heartfelt applause.

The Biblical quote “Spes contra spem” Pannella uses, does not imply an act of faith. Pannella, who is a believer in the human being and in his ability to take on the responsibility of being the change one wants to see happen in the world, seems to use it as some kind of evocative “magic formula”, and not as a “mere” quote from a “sacred text”: he uses it to mean that one needs to be subject of hope rather than invoking hope as an object.

Two days after our visit to the prisons of Niamey and Kollo, and for the first time since the exercise was launched, Niger voted for the UN resolution proclaiming a universal moratorium on executions. In an official meeting in his office, Minister Marou Amadou had predicted with excitement and emotion: “Vous avez mon parole d’honneur” – you have my word of honour. Spes contra spem.

* From 11 to 22 November 2014, Hands Off Cain (HOC) and the Nonviolent Radical Party (NRP) visited three African countries to gather support for a Resolution, which would have been voted by the United Nations General Assembly that year calling for a universal moratorium on executions. The delegation was composed of Sergio D’Elia, Secretary General of HOC, Marco Perduca, UN Representative of the NRP, and Marco Maria Freddi. The missions involved Zimbabwe and the Comoros Islands, and Niger, where the delegation was joined by Marco Pannella, President of the NRP, Matteo Angioli and Stefano Marrella. The reportages by Marco Perduca and Sergio D’Elia, published by Panorama.it, are an account of two important stages of the mission.