government: no permanent national government; transitional, parliamentary federal government

state of civil and political rights: Not free

constitution: 23 September 1979

legal system: no national system; a mixture of English common law, Italian law, Islamic Shari'a, and Somali customary law

legislative system: unicameral National Assembly

judicial system: following the breakdown of the central government, most regions have reverted to local forms of conflict resolution, either secular, traditional Somali customary law, or Shari'a (Islamic) law with a provision for appeal of all sentences

religion: Sunni Muslim

death row:

year of last executions: 0-0-0

death sentences: 52

executions: 20

international treaties on human rights and the death penalty:International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

1st Optional Protocol to the Covenant

Convention on the Rights of the Child (signed only)

Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

situation:

The Penal Code of Somalia represents an amalgam of various legal systems and traditions.

In Somalia, until 1991, there were at least three types of courts: that of the State, that of Islam and the

traditional courts which were all charged with settling disputes between people

of the same clan.

When, in 1991, the “clans” overthrew the dictator Siad Barre, the Country was torn apart by a bloody power struggle

between fighting clans, which has seen thousands of victims.

After thirteen years of chaos, attempts at establishing a government and two years of peace talks held under

the auspices of the international community which sought to consider the

principal divisions between clans, in October 2004, the transitional Parliament

elected Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the new President of the Country and gave life

to a Transitional Federal Government (TFG). The elections were held in Kenya

because Mogadishu was considered too dangerous.

Since then, thanks to institutional power struggles in the Country and rampant corruption, all attempts failed to

bring peace, stability and democracy to Somalia.

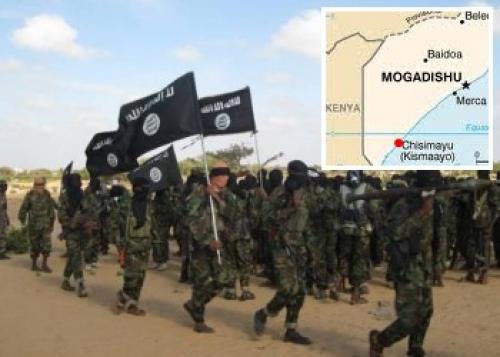

Under the circumstances, the violent insurgency led by Al-Shabaab and other groups like Hizbul Islam became even more

violent, and the role of Islamic tribunals was strengthened, having its

jurisdiction expanded to common crimes with its sentences being difficult to

appeal. The courts were seen by an increasingly larger portion of the

population as the only force capable of bringing order after twenty years of

total chaos.

In Somalia, at the end of 2006, troops of the transition government in Mogadishu defeated the Islamic Courts

with the help of the Ethiopian military. But the rebels took on guerrilla

tactics that proved very hard to combat, and Islamist fighters from the

hard-line Al-Shabaab insurgency run most of south and central

Somalia imposing laws inspired by the most severe conceptions of Islam, while

the UN-backed government only controlled parts of the capital. Many Somali religious leaders and

other Islamic scholars disputed their interpretation and practice of Islamic law. “When a

person is sentenced to being stoned to death, there are several conditions which must be met. This is not

something which can be concluded in two or three days, and there must be

evidence or eyewitnesses who establish criminal identity, but al-Shabaab provides neither clear

evidence nor witnesses. They are killing people senselessly,” Somali religious

leader Sheikh Dahir Abdi Abdul told Somalia Report. "The application of punishment is a matter for the legitimate state, and is not the right of any group, whether it chooses to implement the

death penalty or to implement the hudud provisions," said Sheikh Abdulqadir Somow, spokesman

for the Supreme Council of Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa scholars, part of the

Federation of Sufi Orders in Somalia. Sheikh Somow said Al-Shabaab has committed crimes and

murder against innocent civilians under the guise of spying charges. He said

there is disagreement among Islamic jurists about judgments against people

convicted of spying, but killing them is not endorsed by Islamic law.

"This group has committed more than a crime, and if you look at the way in

which it is killing people, its actions have no legal cover, but are contrary

to Islamic law," he told Sabahionline.

"The Al-Shabaab group is seeking to terrorise Somali citizens with these rulings."

In April 2009, in an attempt at national reconciliation, the Somali parliament unanimously approved a

government proposal to officially introduce Sharia law in the Country. Opposition commanders, particularly

those of the hard-line Al-Shabaab group, had previously dismissed the plan for lawmakers to introduce the Sharia as

“conspiracy against the Islamist fighters and their cause.”

In August 2009, the Transitional Federal Government established a military court to try soldiers accused of

criminal offences. However, the military court functions with no guarantee of

basic fair trial standards, such as the right to have a legal representation in

court and, for those convicted, the right to appeal and seek pardon or

commutation of sentence.

On 13 August 2011, the TFG president, Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, declared a state of emergency in areas of Mogadishu vacated by Al-Shabaab. Under the emergency

decree, signed by the president but not approved by the Parliament, the military court was

given jurisdiction over all abuses committed in areas under the state of

emergency, including jurisdiction over crimes committed by civilians, in

violation of Article 57 of Somalia’s Transitional Federal Charter that

stipulates that military courts should have jurisdiction only over military

offences committed by members of the armed forces. There have been some improvements since 2011,

including an attempt to ensure basic legal counsel, and the re-establishment of

a Supreme Court to hear appeals in late 2012. Yet, concerns remain over the

right to be tried by an independent and competent tribunal, the right to

prepare a defence, and especially the use of military courts to try civilians.

Under international and regional standards, the jurisdiction of military courts

should be limited to offences of a strictly military nature committed by

military personnel. However, the military courts continue to exercise very

broad jurisdiction over individuals and criminal offences.

As of 23 January 2012, according to the military courts, there were more than 50 people in custody including TFG soldiers and Al-Shabaab agents

who had been sentenced to death. Ever since the establishment of the military courts they

have carried out executions although the executions mostly concerned TFG soldiers

who committed crimes.

A new Provisional Constitution was passed in August 2012, which designates Somalia as a federation. Following the end of the interim mandate of

the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) the same month, the Federal

Government of Somalia, the first permanent central Government in the country

since the start of the civil war, was also formed. On 10 September 2012, Somali parliamentarians

elected Hassan Sheikh Mohamud to the country's highest office in the first presidential elections

held inside Somalia in over two decades. Mohamud defeated former Transitional

Federal Government President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed in the second round of

voting, 190 to 79. Lawmakers voted at the Police Academy in Mogadishu, where

271 out of 275 members of parliament were in attendance.

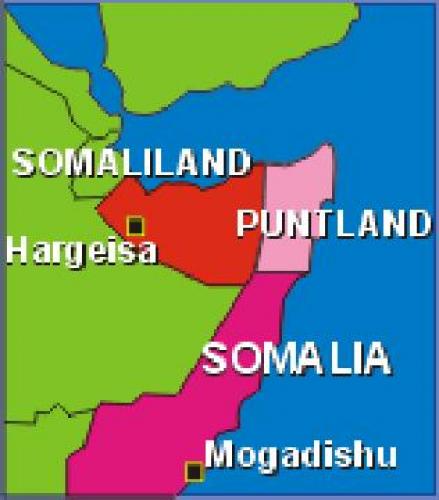

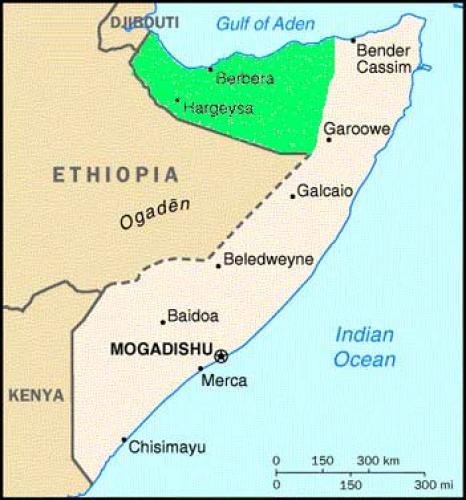

The self-proclaimed Republic of Somaliland is the only part of the ruined Country of Somalia to have

established peace, a Government and a multiparty political system.

Parliamentary elections were held in September 2005 and the new Republic awaits

international recognition. Somaliland, whose judicial system is based on the

old Somali Penal Code, maintains the death penalty, although many local human

rights’ groups have called for its abolition. In recent years, many of those

condemned to death have had their sentences commuted thanks to the payment of

“blood money” (diya) according to Sharia law.

The traditional clan system and customary law Xeer are very strong in the semi-autonomous State of Puntland, and are usually used in

criminal or other proceedings. Under this system, elders serve as judges and

help mediate cases using precedents. The clans help the police and courts in

their work. In case of intentional homicide, there are severe penalties in

terms of both Diya payment and imprisonment. When the clans agree during

negotiations that a perpetrator should be killed, the agreement is taken to

court. The court refers the matter to the president for approval. The president

signs the agreement and returns it to the court. The clans' agreement is final

and cannot be appealed. The police monitor the implementation of the decision

to execute, but it is a relative of the victim who performs the execution. This

will reduce the number of extra-judicial killings taking place in some towns in

Puntland.

At least 27 executions were carried out in 2013, including 15 in the autonomous region

of Puntland. Other 6 executions were carried out in 2014 (as of 25 May). According

to Amnesty International, at least 117 people were sentenced to death in 2013

(8 by the Federal Government, 81 in Puntland and 28 in Somaliland). In 2012, there were at least 7 “legal”

executions carried out by the Transitional Federal Government, and at least 1

carried out in the autonomous region of Puntland. According to Amnesty

International a total of at least 76 people were sentenced to death in 2012. In 2011, there were

at least 11 “legal” executions and at least 37 death sentences were issued. At

least 7 people were executed by the Transitional Federal Government, another 3 in the autonomous region of

Puntland, while one person was executed in Galmudug. In 2010, there were at

least 8 executions and at least 11 death sentences. In 2009 there were no

executions but there were at least a dozen condemnations to death. In 2008,

there have been three executions. In 2007, at least five people were put to

death, almost all sentenced by military tribunals.

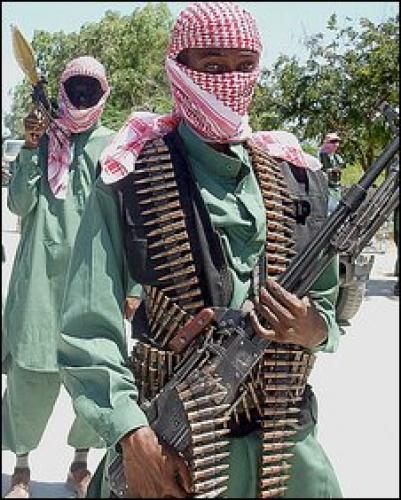

The beheadings carried out by the Islamist extremists of Al-Shabaab – “Youth”

in Arabic – that control part of south-central Somalia are classified as

“extra-judicial executions”. The group seeks to overthrow the western-backed

interim government and take over the Country imposing a rigid application of Sharia. Somalis have been shocked by

the movement's strict interpretation of Islamic law. The movement decapitated

several people on charges of being Christians, spies or apostates of Islam. Sentences

by stoning were carried out once again by the Islamic rebels Al-Shabaab in

2011 and 2012. After the victims are executed, Al-Shabaab members bury them in sites called “the infidels’ cemeteries,” residents of

areas formerly occupied by Al-Shabaab.

On 12 September 2013, some 160 Somali religious scholars issued a fatwa denouncing Al-Shabaab, saying the group had no

place in Islam. Observers say it is the first time Somali religious leaders

have come up with a fatwa against the group. At a conference on the phenomenon of extremism in Mogadishu,

the scholars said it condemned Al-Shabaab’s use of violence. Despite being pushed out of key cities in the past years, it

still remains in control of smaller towns and large swathes of the countryside.

On 18 April 2013, Somali Cabinet Ministers approved the anti-terrorism

bill in an effort to eliminate “terrorist” groups throughout the country.

Cabinet approval of the draft of the anti-terrorism law came after the April 14th

suicide bomb attack at the Court of Banadir that killed more than 30 people and

wounded 58 others, for which Al-Shabaab claimed responsibility. The new law criminalizes any telecom firm or money

remittance agency dealing with members of Al-Shabaab fighters. Hotel owners and car rentals are also

required to identify their clients to see if they are involved in any terrorist

networks.

In March 2014, Human Rights Watch (HRW) released a report detailing how Somalia’s military court proceedings "fall short of

international fair trial standards". Relatives of defendants and

independent observers have very limited access to the hearings, allowing the

court to operate without oversight. A central concern was the speed at which

death sentences have been carried out, preventing defendants from filing an

appeal and the president to review the case for a possible pardon or

commutation. Under international law, the death penalty is permitted only after

a rigorous judicial process - a fair trial in which the defendant has adequate

time to prepare a defence and appeal the sentence, among other requirements.

Somalia’s new military court chairman, Col Abdirahman Mohamed Turyare, has

boasted of flagrant violations of these requirements under international law.

On 11 August, he told the media that his court was waging a "new war

against terrorists." “Our role is to firmly impose treason laws against

the terrorists who cause problems,” he said in an interview with sabahionline.

Turyare added that parents of Al-Shabaab suspects would be arrested and he

claimed some were already in detention. "It is failure to exercise responsibility

of parent-ship. It is your responsibility as father or mother to report to the

police that your children are missing or went to terrorist group," he

said. In 2014, as of 3 August, at least 9 Islamic militants

convicted of terrorism were executed in Somalia.

On 21 September 2011, in its response to the recommendations received under the Universal Periodic Review of the UN

Human Rights Council, the TFG stated that “the Government does not want the

practice of death penalty to add to more loss of life… While the death penalty

is currently imposed for the most serious crimes, the Government undertakes to

work towards declaring a moratorium on the death penalty with a view to its

eventual abolition.”

On December 18, 2014, Somalia co-sponsored and voted in favour of the Resolution on a Moratorium on the Use of the Death

Penalty at the UN General Assembly such as in 2012. In 2008 and 2010, it voted

in favour.